For generations, the entertainment industry has portrayed scientists as morally (and often socially) challenged atheists who are more likely to own a lab coat than a soul, and science as a cold, blunt instrument that gives no quarter to feeling or faith. Neil deGrasse Tyson’s “God of the gaps” argument dovetails with this imagery: God exists to explain the unexplainable, so the more we know, the smaller the gaps become in our understanding and the less we need God. (Editor’s note: We still love Neil deGrasse Tyson.)

Is this accurate, though? Tyson isn’t the first scientist to weigh in on religion. A hundred years ago, Albert Einstein was often questioned about his personal relationship with the universe. To Einstein—who believed in God but not organized religion—God was a mystery too vast for us to comprehend, not like a man magnified but a presence that inspires awe when we observe the laws of nature. Other scientists over the generations have believed in Spinoza’s God, who is revealed in the orderly harmony of what exists, not one who is concerned with fates and actions of human beings. Still other scientists have viewed God as more of a spiritual connection with the universe than an entity who grants wishes; and to them, religion might provide boundaries, traditions, and structure for how to express this connection, not necessarily directions for how to interpret scripture. And for others still, over the last decade alone, Nobel Prizes have been awarded to scientists who are devout Jews, Catholics, and Muslims, and in the US alone, devoutly religious scientists have held some of the highest-ranking positions in research leadership and administration.

The raw numbers, however, do reflect a large difference between scientists and the general public on the question of religious belief. According to a 2009 Pew Research poll, about 33% of American scientists (down from 43% in the early 1900s) believe in God (and an additional 18% in “a universal spirit or higher power”) compared to 83% of the American public.

Source: Scientists and Belief | Pew Research Center

In a more detailed analysis published in 2007 (Religion among Academic Scientists: Distinctions, Disciplines, and Demographics)—which includes fewer participants than the Pew survey but a more detailed breakdown of beliefs— the number of scientist believers might be somewhere between six and 35%, depending on whether the answer is “I believe in God sometimes,” “I have some doubts, but I believe in God,” and “I have no doubts about God’s existence” (added together, these responses roughly equal the Pew total of 33%). This compares with the 63%, not 83%, of the general public who believe absolutely in the existence of God as determined by a different Pew poll (Belief in God – Religion in America: U.S. Religious Data, Demographics and Statistics), with wide variation by factors like education, income, gender, and faith. Indeed, variation by education in this Pew poll is particularly striking, with only nine percent of respondents who hold post-graduate degrees saying they believe in God with absolute certainty (this nine percent figure is roughly consistent with the 2007 analysis mentioned previously).

Why does any of this matter? Why should we question the religious beliefs of scientists or imply it matters a whit whether these beliefs are acceptable to the public? It doesn’t, obviously. At the same time, it’s important to try to better understand this confluence of perceptions because the image of science matters. When those who seek to discredit science (or at least discredit fields like Evolution or climate change) on the grounds that science is an “elite,” Godless pursuit neither informed by faith nor responsive to the perspectives of communities of faith, science needs to understand this criticism and understand how to communicate with its critics. Researchers who study evolutionary biology, so goes the criticism, must be hostile to religion because their work directly challenges the idea that man was created by God, or scientists engaged in these studies must place a higher value on the search for truth than on respecting the moral philosophies that bind society together (how we determine which of these philosophies are universally recognized or binding is another question).

These kinds of perceptions can fuel hostility toward science, especially among groups who value the moral and social framework of religion over the allegedly “Godless” and objective framework of science. The perceptions also promote the contention that religion is a necessary component of faith, feeling, ethics, morals, and other sensitivities that form the scaffolding of our concern about the human condition. To suggest that scientists who devote their lives to curing disease are somehow less feeling or moral than religiously observant nonscientists is a distortion of truth and logic.

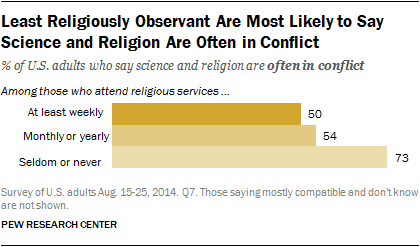

Similarly, these attitudes can fuel blowback among scientists that all people of faith must be science deniers, and are therefore not welcome in dialogue about the proper role of science in public policy. In fact, in a 2015 survey of two thousand US adults conducted by the Pew Research Center, people of faith were revealed to have many different opinions about science, and these differences might vary by many measures such as denomination and level of commitment, with the least observant being the most likely to feel that religion and science are in conflict. In short, it is just as wrong to stereotype the religious views and sensitivities of scientists as it is to stereotype the scientific literacy of the religious public.

Source: What U.S. Religious Groups Think About Science Issues

This topic has much more nuance and texture that deserves our focus and attention in science communication. But for the purposes of this profile, we wanted to include a few stories from scientists describing their personal insight into how science and religion coexist in the real world. We are grateful that Dr. Howard Smith and Dr. Janel Curry agreed to contribute to this article. Dr. Smith is senior astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the author of Let There Be Light: Modern Cosmology and Kabbalah, a New Conversation Between Science and Religion (New World Library, 2006). Dr. Curry is a geographer, and president of the American Scientific Affiliation.

This topic has much more nuance and texture that deserves our focus and attention in science communication. But for the purposes of this profile, we wanted to include a few stories from scientists describing their personal insight into how science and religion coexist in the real world. We are grateful that Dr. Howard Smith and Dr. Janel Curry agreed to contribute to this article. Dr. Smith is senior astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and the author of Let There Be Light: Modern Cosmology and Kabbalah, a New Conversation Between Science and Religion (New World Library, 2006). Dr. Curry is a geographer, and president of the American Scientific Affiliation.

Dr. Smith argues that science and religion are not only compatible, but that endeavoring to understand both is essential to developing a fuller perspective on the meaning of life. “I urge all my readers,” says Smith, “both those who are religiously inclined or scientifically minded, to be open to the wisdom and insights of all seekers after the truth, on all paths. A deeply religious person is one who is open, not closed, to the unfolding wonders of God’s world as science uncovers new phenomena and connections. A committed scientist is one who is open, not closed, to truth even from other traditions, insights about the world, and to the manifold blessings we enjoy. Is this difficult to do? Yes, very. But it is the pathway to deeper understanding.”

Dr. Smith argues that science and religion are not only compatible, but that endeavoring to understand both is essential to developing a fuller perspective on the meaning of life. “I urge all my readers,” says Smith, “both those who are religiously inclined or scientifically minded, to be open to the wisdom and insights of all seekers after the truth, on all paths. A deeply religious person is one who is open, not closed, to the unfolding wonders of God’s world as science uncovers new phenomena and connections. A committed scientist is one who is open, not closed, to truth even from other traditions, insights about the world, and to the manifold blessings we enjoy. Is this difficult to do? Yes, very. But it is the pathway to deeper understanding.”

Dr. Curry agrees. In her faith, knowledge of science is a gift of God, and being willfully ignorant of this knowledge or misrepresenting it to fit our belief systems is completely misguided. By the same token, she adds, “I’m not any more comfortable with blind faith in science than I am with blind faith in religion. Both science and religion have important roles, and both must constantly work hard to make sense of the world.”

Where are the boundaries, though, between science and faith? Paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould has written that science and religion each represent different areas of inquiry, and are in fact “non-overlapping magisteria.” For example, while science deals with the big questions, religion deals with our personal connections to these questions. Or science deals with questions of how, and religion with questions of why. Or even proximate and distal differences—science deals with the here and now, and religion with longer questions. Former NIH director Francis Collins has similarly written that “Science’s domain is to explore nature. God’s domain is in the spiritual world, a realm not possible to explore with the tools and language of science. It must be examined with the heart, the mind, and the soul” (see the National Academies report linked below). In all these characterizations, science is portrayed as evidence-based and responsive to change, while religion is neither.

Dr. Smith takes issue with this characterization. Says Smith, “I don’t think an approach that attempts to divide the world into camps by looking for differences in their style or content is a particularly good one to grow either spiritually or scientifically. Instead, we should concentrate on the insights each brings to the other. After all, the essence of the world is its unity, not its disparity. The differences of style are not all that important and focusing on them can be a distraction. Also, religion can and does also ask ‘big’ questions and the ‘how,’ and science can and does also ask about personal matters and the ‘why.’ Religious traditions discuss the creation of the world, and scientific disciplines study human qualities from altruism to love. My approach is not to search for differences between science and religion, but rather to find ways to learn from both.”

Still, for many, understanding where to turn for answers can be perplexing. Participation in organized religion is declining worldwide, and even for the non-religious, science doesn’t necessarily offer the same scaffolding for dealing with life’s uncertainties and questions about our existence. The solution, says Smith, isn’t about either/or, but both. “For me, the wonders of science, as I appreciate them every day (some as new discoveries, and others as previously known but newly understood), reinvigorate my spiritual life with wonder, appreciation, and gratitude.” For Curry, her scaffolding is all about community. “Our search for truth,” she says, “takes place in communities that have developed skills, traditions, practices and terminologies that allow for deeper communal discussion and understanding. This is true for both religion and science. Our search for truth is not solitary. Our search for truth involves all of us, and is all-encompassing.”

Additional reading:

Glenn is Executive Director of the Science Communication Institute and Program Director for SCI’s global Open Scholarship Initiative and Carbon Dioxide Removal Action Network (CDRANet). You can reach him at ghampson@sci.institute.