Scholarly publishing has been in a state of transition for several decades now, driven by the rapid evolution and expectations of our digital society, the explosion and specialization of research over this period of time, and importantly, a concerted effort—led in large part by the open access movement—to make more of the world’s research information “open.” Exactly what this means and how to get there from here has been difficult to define and implement. Many new ideas and opportunities have surfaced along with new stakeholders, processes, and requirements, but are the open solutions we’re pursuing being adopted fast enough and widely enough? Are these solutions the right ones? What are the options? What are the sticking points? Are we satisfied with the current state of all the other issues tied into a Gordian knot with open, including embargoes, peer review, digital preservation, data access, journal costs, impact tracking, and institutional repositories? Who should get to decide these questions and why?

Different stakeholder groups have worked on these and related issues for years, but never together in a broad, collaborative or global way. And as different solutions and approaches have rolled out, confusion and fragmentation between different stakeholder groups has reached the point where all stakeholders acknowledge that finding a clear path forward is vitally important.

In October of 2014, the National Science Communication Institute (nSCI) convened and moderated a three-month online conversation of around 100 delegates to discuss the future of open. In February of 2015 this group published its findings, which included a recommendation to form an international, multi-stakeholder effort to work together on needed reforms in scholarly publishing. The Open Scholarship Initiative (OSI) was up and running by June of 2015 thanks to early support from the United Nations (UNESCO) and George Mason University. Between June and March 2016, 225 delegates to the inaugural OSI conference were recruited and instructed and by the time of their first meeting in April of 2016, these delegates had already shared hundreds of emails covering a wide variety of topics and read many hours of background materials. Their meeting in April focused on the foundational questions of scholarly publishing. What is open? What is publishing? What are the moral dimensions of open? Why do authors participate in this system? What about peer review, impact factors and embargoes? A full list of the questions covered at OSI2016 is in Annex 1.

Each of these questions was addressed by diverse 10-12 person teams. Some teams were more diverse than others, but overall, the conference was balanced by design to represent a broad swath of perspectives in scholarly publishing. Importantly, almost all delegates were high level representatives empowered to speak on behalf of their organizations (including universities)—not only people who were interested in this topic, but people who were capable of driving change within their organizations and entering into partnerships with other groups.

OSI2016 was first event to bring together such a large and diverse group of high level delegates to discuss the future of scholarly publishing—196 delegates in all attended, representing 12 countries and 15 stakeholder groups across 184 institutions, including 50 major research universities (25 percent of delegates), 37 scholarly publishers (19 percent of delegates), 24 government policy organizations (12 percent), 23 scholarly libraries and groups, 23 non-university research institutions, 17 open knowledge groups (9 percent), eight faculty and education groups, and more. Future meetings will be at least the same size or larger, and will include even more international representation. Delegate fees provided the largest source of funding for this event (34 percent, or US$58,000 of the total US$169,000 budget), followed by US$48,000 from UNESCO (28 percent), US$27,000 from six publishing companies (16 percent), US$20,000 from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (12 percent), and US$15,000 from four other sponsors (10 percent). More details are available on the OSI website at http://osinitiative.org.

The reports that came out of this conference are an opening salvo of collaborative thinking on scholarly publishing reform. They aren’t intended to be final, fully developed proposals. They are, however, intended to help lay the groundwork for how the full scholarly publishing stakeholder community can work together to create a better future. Some of these proposals are remarkably bold and insightful; others do a magnificent job of capturing the complexity of the challenges ahead; still others concede that more study is needed. These are all complex questions requiring thoughtful and deliberate conversations. We hope these proposals can be discussed with a wider stakeholder audience, and after more feedback, can be fine-tuned into workable action plans—if not this year then certainly within the next few years. Subsequent OSI delegate groups and conferences will focus on implementing these proposals, and follow through on progress, impacts, needed adjustments, and the torrent of new ideas and opportunities that will be unleashed once progress starts occurring at a fast pace.

The ideas in these papers can be grouped into two main categories: Overarching themes and specific recommendations. The overarching themes will help inform OSI about where to focus next—where to find consensus, and what issues are most fundamental to the success of reform efforts. Themes from OSI2016 can be characterized as follows:

- Acknowledging: Scholarly publishing is changing, and this presents opportunities and challenges.

- Describing: Some of the change that is happening involves shaking up the current system to utilize publishing tools and approaches that may be better suited to an Internet-based information world. But not all current and needed changes fall into this category. Indeed, some of the most needed changes do not.

- Proscribing:

- Some change will need to involve reforming the ancient, stagnant communications culture inside academia, where old publishing methods, measures and perceptions drive author choices and are used as proxies for merit when evaluating grant awards and tenure decisions. And some will need to involve examining our own biases that publishing is a binary proposition involving either open or closed, subscription or green, right or wrong. Open, impact, author choices, peer review and other key concepts all exhibit a range of values. Creating new, non-binary measures for some of these values (as proposed by several workgroups) may be helpful insofar as allowing stakeholders to focus on improving areas most in need of change, and comparing progress and best practices across disciplines, institutions, publishing approaches, funders, and so on.

- Any widespread change is going to require a widespread, coordinated effort. There are simply too many stakeholders with different interests and perspectives who influence different decision points. No single stakeholder or group will be able to affect this kind of change unilaterally.

- Additionally, we don’t have a clear, coordinated action plan for improving open. What needs to happen today, tomorrow and the day after? Who are the actors, what are the mileposts, what are the likely impacts, and how do we measure success?

- How do we make these reforms in response to needs and concerns of authors rather than in spite of authors?

- How do we make changes across disciplines (which have different needs) and that also effectively build on the efforts of the many stakeholders in this space?

- How do we reform the system without losing its benefits?

- How do we move from simply repairing dysfunction to creating a more ideal publishing world and reaping the benefits that such a world could provide in terms of participation, efficacy, efficiency, and discovery?

- More standards and norms would be helpful as we move forward, as well as answers to a number of key questions.

To the skeptic, it may not seem significant that 225 high level delegates agreed that change is happening, the challenges are great, and that clear, coordinated action is needed. But to the optimist, the exact opposite is true: It is, in fact, remarkable that publishers and policymakers, open advocates and skeptics, funders and library heads, scientists and humanities leaders all agree that the scholarly publishing system needs to be repaired as a group and that we need a foundation for action. No one is throwing up their hands in despair, no one is walking away from the table, and no one is threatening to force change on the other. Indeed, the general sense among OSI2016 delegates is hopeful and enthusiastic, if a little uncertain about what comes next (see Annex 2).

Some of the key specific recommendations developed by the OSI2016 are listed below and will be circulated for feedback. Bear in mind these recommendations came from high-level representatives of multi-stakeholder workgroups. They aren’t just pie-in-the-sky proposals, but in many cases bold starting points for conversation that major publishers and research universities may be willing to stand behind:

| Workgroup | Key action items |

|---|---|

| What is publishing? (1) | Explore disaggregating the current services provided by publishers (such as filtering, editing, dissemination, registration, and so on) and how current scholarly publishing stakeholders might be incentivized to embrace these changes. |

| What is publishing? (2) | Explore ways to change the publishing culture inside of academia, including systems of academic recognition and reward. Identify unmet author needs, and gaps in evidence and knowledge, develop disciplinary approaches, and use pilots rather than one-size-fits-all approaches. |

| What is open? | The scholarly community’s current definition of “open” captures only some of the attributes of openness that exist across different publishing models and content types. We suggest that the different attributes of open exist along a broad spectrum and propose an alternative way of describing and evaluating openness based on four attributes: discoverable, accessible, reusable, and transparent. These four attributes of openness, taken together, form the draft “DART Framework for Open Access.” This framework can be applied to both research artifacts as well as research processes. |

| Who decides? |

|

| Moral dimensions of open | In this transition period, we need to encourage a period of exploration and grace in the search for new models, while being prepared to judge such efforts by the highest moral standards. We must consider, for example, whether a particular invention maximizes the new digital affordances in order to increase universal access. We consider it our responsibility to make judgements about the morality of acts, artifacts, systems, and processes, but not on the morality of people and organizations. |

| Usage dimensions of open |

|

| Evolving open solutions (1) |

|

| Evolving open solutions (2) |

|

| Open impacts | Openness scores should be developed, as well as utilization and economic impact measures. Ideas are proposed for what would be included in the baselines of each such evaluation. More research is needed and proposed, perhaps as standing (ongoing) OSI efforts. |

| Participation in the current system |

|

| Information overload & underload | Solving these challenges will require all stakeholders to be both deliberate and inventive, ideally within a framework of open collaboration built upon common values, shared metadata, sound standards, and commitment to a far more open system of scholarly endeavors. |

| Repositories & preservation |

|

| Peer review |

|

| Embargoes | A project is proposed to study and reform the current embargo system. The stages of this project are as follows:

|

| Impact factors |

|

| At-large |

|

Drawing from this summary, it’s possible, then, that OSI2017 and the OSI efforts between now and then may end up focusing on these key points:

- Strategy and/or partnership agreements to work aggressively to change the culture of communication inside academia

- Linked to this, lay the groundwork for a promotion and tenure reform effort (a framework agreement with stakeholder partners to disentangle the influence of journal publishing)

- Create and pilot new spectrum measures for “open” and impact (for open, incorporate attributes identified by the open impacts group into the DART framework developed by the “What is Open?” group)

- Create a working group to recommend tools to replace the journal impact factor

- Publishing services disaggregation pilot or study

- Embargo study (does immediate access hurt subscription revenue?)

- Global flip study (are APC’s the right model?)

- Impact study (what are the economic impacts of open? What does impact currently look like? )

- Repositories integration solution pilot or study

- A study to figure out which scholarly publishing stakeholders can work together on these and other efforts (and how), including partnership agreements, commitments

- New funding models, such as a venture fund that can allow more support for joint efforts, or improving the flexibility of library budgets (e.g., by examining the efficiency of “big deals”).

- Standards development (including a global study of norms and best practices, and also including more clarity and consistency in rules and regulations from publishers and communication of the same—e.g., a way to clearly identify which papers fall under which embargo period).

- Radical interoperability and infrastructure solutions

- Peer review clarification (different needs for different stages)

- Expand the sounding board: Make sure that more key stakeholders outside this conversation weigh in (more authors, scientists, voices from the Global South, and university provosts), if not as part of OSI (due to lack of time or interest) than by some other means.

A final determination about which efforts will be followed this year will be completed by the Fall of 2017 after the workgroup papers have been vetted by the broader stakeholder community and the OSI planning groups can develop a better sense of this program’s trajectory for 2016 and beyond. In the meantime, the versions of record for these papers are published on the George Mason University website at http://journals.gmu.edu/osi. Comments are welcome on the html versions of these papers posted at http://osinitiative.org.

Overarching themes and recommendations also emerged from this conference regarding the OSI effort itself. These will be taken under advisement and used to improve future conferences.

OSI2016 was an important step toward developing collaborative solutions to scholarly publishing that are widely embraced, effective, and sustainable. It is commendable that this stakeholder community has started to engage in this process. Long-term stalemates don’t serve a purpose, and in fact in the case of science research, they are increasingly damaging as they contribute to uncertainty about the road ahead. Developing a broad, collaborative, global approach is critical—now more than ever—not only for the future of research funding, public policy, economic development, global information access and equity, and discovery, but also for the future efficiency, effectiveness, and sustainability of research communication.

OSI2017 will take place April 18-21, 2017 at George Washington University in downtown Washington, DC. For more information, please visit the OSI website at http://osinitiative.org.

Annex 1: OSI2016 workgroup questions

What is publishing?

What do we mean by publishing in today’s world? What should be the goals of scholarly publishing? What are the ideals to which scholarly publishing should aspire? What roles might scholarly publishers have in the future? What scenarios exist where publishers continue to play a vital role but information moves more freely? What impact might these reforms have on the health of publishers? Scholarly societies? Science research? Why?

What is open?

There is a broad difference of opinion among the many stakeholders in scholarly publishing about how to precisely define open access publishing. Are “open access” and “open data” what we mean by open? Does “open” mean anything else? Does it mean “to make available,” or “to make freely available in a particular format?” Is a clearer definition needed (or maybe just better education on the current definition)? Why or why not? At present, some stakeholders see public access as being an acceptable stopping point in the move toward open access. Others see “open” as requiring free and immediate access, with articles being available in CC-BY format. The range of opinions between these extremes is vast. How should these differences be decided? Who should decide? Is it possible to make binding recommendations (and how)? Is consensus necessary? What are the consequences of a lack of consensus?

Who decides?

Tied to this question of who should decide the future of open access, who should have the power to make changes to scholarly publishing practices? Do these powers flow from publishers, institutions, tenure committees, funding agencies, authors, or all of the above? All of the above? None of the above? What are the pros, cons, and consequences of different institutions and interest groups developing and implementing their own solutions (even the one-off variety)? Is federal oversight needed? Global coordination (through an organization like UNESCO)?

What are the moral dimensions of open?

Does society have a moral imperative to share knowledge freely, immediately, and without copyright restriction? A legal imperative? Why or why not? What about research funded by governments? Corporations? Cancer research? For that matter, is our current mechanism for funding scholarly publishing just or unjust? What other models are there? What are the pros and cons of these models? What is the likelihood of change?

What are the usage dimensions of open?

What are the usage-related challenges currently faced by open efforts? For instance, open data is intriguing in principle, but in reality, making underlying data open can be problematic, conflicting with the need for research secrecy (whether driven by the desire to be first to publish, or the desire of funders to hold onto data to protect future discovery potential), the potential for misinterpretation by other researchers, and so on. Publishing clinical trial data in open formats is also intriguing but would run afoul of many current consent agreements, particularly older consents. Open access is similarly challenged in some instances by a conflict between which version of papers is allowed appear in open repositories. What is the value of archiving non-final versions? What are the range of issues here, what are the perspectives, and what might be some possible solutions?

Evolving open solutions

Are the scholarly publishing tools we’re using today still the right ones? Is the monograph still the best format in the humanities? Is the journal article still best in STM? These products can be difficult to produce and edit, nearly impenetrable to read, and — as in the case of clinical research information — they aren’t necessarily the best-suited formats for capturing every piece of necessary information (like protocols and datasets in medical research) and showing how this information is all connected to other scholarship. What other formats and options are being considered or used? What are the prospects of change? How about the stakeholder universe itself? How are roles, responsibilities and expectations changing (and where might they end up)? Are we “settling” on half-measures or on the best possible solutions?

Open impacts

How fast is open access growing? Is this fast enough? Why or why not? What are the impacts of currently evolving open systems? For instance, are overall costs being reduced for scholarly libraries? Is global access to scholarly information increasing? What about in the Global South? What is the impact in this region of increasing adoption of the author-pays system? What pressures is the move to open placing on institutions and systems and what are the costs/benefits?

Participation in the current system

Do researchers and scientists participate in the current system of scholarly publishing because they like it, they need it, they don’t have a choice in the matter, or they don’t really care one way or another? What perceptions, considerations and incentives do academicians have for staying the course (like impact factors and tenure points), and what are their pressures and incentives for changing direction (like lowering publishing charges)?

Information overload & underload

Information underload occurs when we don’t have access to the information we need (for a variety of reasons, including cost) — researchers based at smaller institutions and in the global periphery, policymakers, and the general public, particularly with regard to medical research. Overload occurs when we can access everything but are simply overwhelmed by the torrent of information available (not all of which is equally valuable). Are these issues two sides of the same coin? In both cases, how can we work together to figure out how to get people the information they need? Can we? How widespread are these issues? What are the economic and research consequences of information underload and overload?

Preservation, repositories & mandates

Are we satisfied with the current state of global knowledge preservation? What are the current preservation methods? Who are the actors? Is this system satisfactory? What role do institutional repositories play in this process? What does the future hold for these repositories (taking into account linking efforts, publishing company concerns about revenue declines, widespread dark archiving practices, and so on)? Would new mandates help (or do we simply need to tighten existing mandates so they actually compel authors to do certain things)? And how do versions of record figure into all of this — that is, how do archiving policies (with regard to differences between pre-journal and post-journal versions) affect knowledge accuracy and transfer?

Peer review

Managing the peer review process is one of the major attractions and benefits of the current publisher-driven publishing environment. Would it be possible to maintain peer review in different system — perhaps one where peer review happens at the institutional level, or in an online-review environment? How? What is really needed from peer review, what are the reform options (and what do we already know about the options that have been tried)?

Embargos

In an information system where so much information is destined for subscription journals, the assumption has been that embargos allow publishers time to recoup their investments, and also allow the press time to prepare news articles about research. Is this assumption warranted? Why or why not? Is the public interest being served by embargos? What about by embargos on federally-funded research? Are there any facts or options that haven’t yet been considered to address the concerns animating the embargo solution?

Impact factors

Tracking the metrics of a more open publishing world will be key to selling “open” and encouraging broader adoption of open solutions. Will more openness mean lower impact, though (for whatever reason — less visibility, less readability, less press, etc.)? Why or why not? Perhaps more fundamentally, how useful are impact factors anyway? What are they really tracking, and what do they mean? What are the pros and cons of our current reliance on these measures? Would faculty be satisfied with an alternative system as long as it is recognized as reflecting meaningfully on the quality of their scholarship? What might such an alternative system look like?

Annex 2: OSI2016 Delegate survey

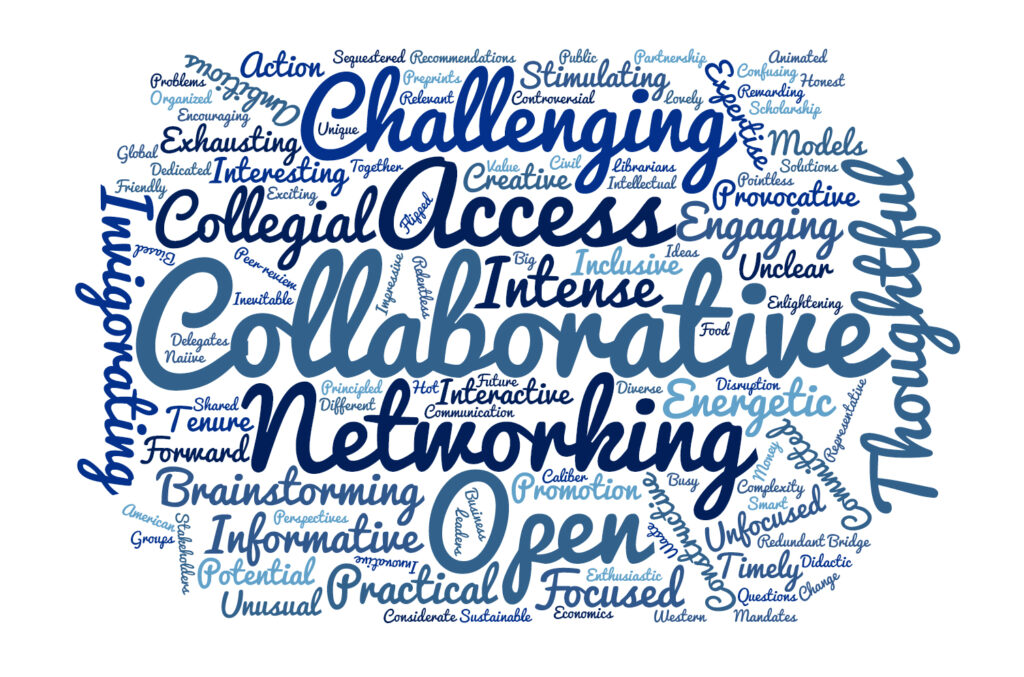

In a survey of delegates (with 49 respondents) completed shortly after the OSI2016 conference, most rated the success of this conference at a 4 on a scale of 1-5 (with 1 being poor and 5 being outstanding). The following word cloud was created by participants, who were asked to list five words that best described this event to them: