According to the world’s most influential open access policies, only certain types of information outputs are genuinely open. In practice, however, there are actually many types of open access outcomes and solutions. A more flexible, evidence-based approach to creating open access policy will better meet researchers’ requirements and also reduce the unintended consequences of our current policies.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The most influential open access policies in the world today are founded on the belief from the early 2000s that only specific types of information outputs are truly open. In this ideology, all other types of outputs (such as free to read but still copyrighted) are unacceptable, particularly for academic journals.

After seven years of global, multi-stakeholder engagement and research—during which our understanding of the global information landscape has evolved a thousand-fold from the early 2000s—the Open Scholarship Initiative (OSI), in collaboration with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), has reached the opposite conclusion: that openness has many definitions and outcomes, and that many different open solutions are working well in modern research communication. In fact, some of today’s most robust and promising open solutions would not even be considered open by the ideology of the early 2000s.

As policymakers around the globe move forward with the challenge of making research more accessible, it is crucial that these efforts be based on solid, democratic, fact-based foundations. Particularly, policymakers should pay close attention to what researchers need, what information sharing solutions are already working in the research world (including solutions that do not fit common definitions of open), and the negative unintended consequences of our current open policies.

UNESCO has long argued that equity should be a pillar of this next-generation open policy framework. OSI has proposed that doing something with open should be a second pillar, treating open as a tool to help research succeed rather than as an end in itself. OSI’s 2022 research communication surveys indicate that the majority of researchers agree with this perspective and methodology.

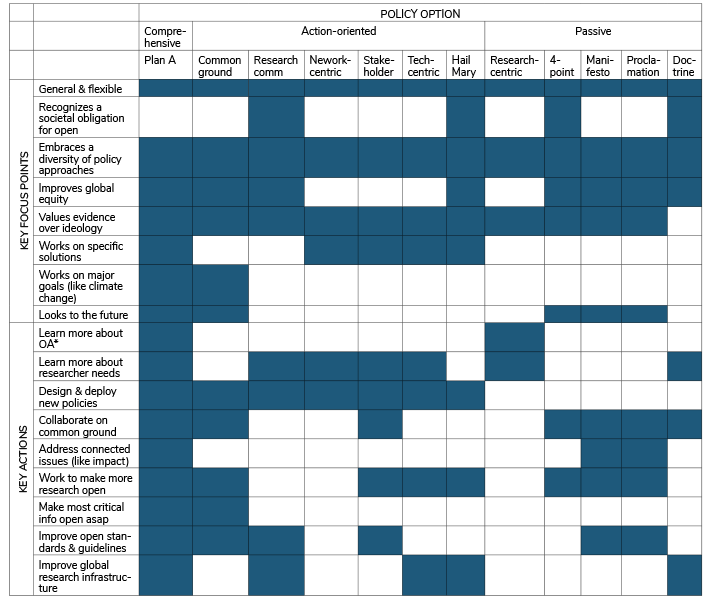

Reconsidering our open policies does not necessarily mean abandoning Plan S, the Nelson Memo, the UNESCO open science policy, or major transformative agreements. In any case, these policies are all evolving gradually in response to feedback and market pressures. Rather, it suggests that in the future, we should also develop broad, inclusive, flexible, evidence-based policies as part of a tapestry of open options and approaches. Doing so will benefit researchers and societies worldwide, improve global equity in research and research communication, allow the world capitalize on the full potential of open research, and help prevent research from fracturing along regional and ideological lines.

INTRODUCTION

The Open Scholarship Initiative (OSI) is an international group of leaders and experts in scholarly communication. Approximately 450 individuals have participated in group discussions since 2015, representing over 250 research institutions from 32 countries and 18 stakeholder groups. UNESCO, non-profit foundations such as Sloan, commercial publishers and publishing industry groups, scholarly societies, universities, scholarly communication experts, and participants themselves (by way of conference fees) have supported OSI’s work.1

OSI has served as an open policy observatory, facilitating direct communication between high-level leaders in scholarly communication, and synthesizing policy recommendations for UNESCO’s consideration based on our group’s extensive knowledge. Our policy recommendations have always been more a collection of perspectives than a consensus opinion, given that we represent so many diverse global regions and differing points of view. For example, when we issued a generally negative critique of Plan S in 2019 due to how it would widen the gap between high and low income countries by replacing paywalls with “playwalls” (i.e., by eliminating subscription access to published research and replacing it with a system where researchers are charged for publishing their findings), roughly a third of OSI participants still supported Plan S with minor or major modifications, while another third did not (Hampson 2019).

These honest differences of opinion exist not only within OSI but within the broader scholarly communication community as well, where some are cheering the current state of open access policies like Plan S, others are urging a more thoughtful and restrained approach, and still others are resigned to the fact that rapid change is happening and are just trying their best to adapt. On social media, these differences of opinion frequently manifest as a battle between good and evil, between those who support rapid reform for the greater good and those who support a status quo characterized by entrenched dysfunction and profiteering.

In reality, though, we are all working toward the same goal: A future where we can do more with research because more research is open and accessible. There are some who want to act now, and others who are committed to finding solutions that truly work for researchers everywhere, not just in the United States and the European Union. Our commitment to working for more inclusiveness and equity is what best defines OSI’s work. Generally speaking, this challenge has appealed to scholarly communication analysts (many of the world’s leading scholarly communication experts have contributed to OSI’s work) but has frustrated those on the far right and far left. Open access (OA) critics have not engaged much with OSI over the years, fearing reputational damage to their careers and institutions by speaking negatively about OA reform ideas and policies, while those who are morally outraged by publisher profits have not engaged much with OSI because OA reforms are, in their mind, a social justice issue with a clear cause and clear solution. For these OA supporters, debate equals appeasement.

To-date, OSI’s authors have published six policy perspectives (including this one) that detail the group’s findings and recommendations. Our first policy perspective, published in March 2019, analyzed the pros and cons of Plan S and suggested that the organizers (cOAlition S) modify their plan to prevent the kinds of unintended consequences we’re currently witnessing with regard to growing inequity between researchers with large publishing budgets and those without. The second policy report from OSI, which was published in April 2020, examined the common ground for policymaking in this space. OSI argued, based on our internal discussions, conference proceedings, and original research, that there are numerous areas of common ground in this community, and that working together on these areas was the most rational approach to policymaking. OSI’s third report, published in June 2020, served as an introduction to OSI’s participation in UNESCO’s open science policy initiative. In this document, OSI provided UNESCO with extensive research on how open science is variously defined and what global open science policies should look like (OSI later participated in UNESCO’s regional consultative meetings and served as an official observer during the final passage of this policy). The fourth policy perspective from OSI, published in February 2021, investigated the technical and policy overlap between all open solutions, including open access, open data, open code, open government, open educational resources, open science, and open methods. This original research led us to the conclusion that the most effective framework for inclusive open solutions policies will be built on a foundation of achieving common goals, such as working together to cure cancer by creating open policies and resources that enable more information of all types to flow between cancer researchers, as opposed to thinking of open as a way to collect information in text, data, or code format. OSI’s fifth report, published concurrently with this report, summarizes the results of its 2022 researcher surveys.

This sixth OSI policy perspective is, in a sense, the culmination of our five previous OSI reports, bringing together their observations and recommendations. In this document, we will reiterate that APCs are harmful and that ideologically-based policies limit the potential of open (OSI Policy Perspective 1); that common ground is abundant and should be our primary policy focus (Policy Perspective 2); that open science policies are an obvious vector for change, but these policies must be grounded in evidence and make sense to researchers (Policy Perspective 3); and that developing broad, flexible, long-term, goal-oriented strategies is essential (Policy Perspectives 4 and 5). In building our case, we will also summarize the key recommendations of OSI participants since 2015 and note how the results of our global surveys of researchers in 2022 support these recommendations.

We believe the observations and recommendations in this report have withstood scrutiny and can serve as the foundation for a new generation of open research policies that are more effective and sustainable than current policies. This claim may appear overly confident. After all, current open access policymaking efforts are continuing unabated, and countries have an abundance of existing policies to choose from without considering new policy frameworks from OSI. As we will discuss in the introduction of this report, however, many of these policies, particularly those of global significance, are not based on evidence or vetted through democratic policymaking processes, as we would expect for sound public policy. A weak foundation is only part of the problem; failing to understand the needs and perspectives of researchers is also a major flaw.

The recommendations in this report describe a range of global open access policies that can be used as templates by researchers, institutions and countries around the world. If you have any questions or would like to provide feedback on this report, please email OSI program director Glenn Hampson at [email protected] by August 31, 2023.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Walt Whitman, the American bard of democracy, noted 150 years ago that democracy isn’t just about voting. It’s also about respecting different points of view in all walks of life.

Representative democracy was a nascent and revolutionary form of government in Whitman’s time. Today, about two-thirds of the world’s countries are democratic. In most of these countries, when it comes to making public policy, democratic principles are the ideal: Experts convene to study an issue, they invite broad and representative public comment to inform their deliberations, and they draft thoughtful recommendations for policymakers and elected politicians to consider. Some policies get codified into law; other policies are amended or disappear entirely over time.

The reality, of course, is that policymakers aren’t robots. Rather, they are individuals who enter the arena of public policy with their own opinions, biases, and motivations. In addition, policymakers are not independent of political leaders. Even though one of the most important characteristics of the modern administrative state is that public servants strive to be impartial and objective, politicians sometimes task administrators with “color by number” policymaking rather than building policy from the ground up, using supplied “facts,” or implementing predetermined partisan solutions. Even when expert policymaking processes are adhered to, political judgment frequently trumps expert recommendations, and interest groups focus more on demonizing opposing viewpoints and misrepresenting facts than on finding common ground and workable solutions.

In the US, this is the history of much high-profile public policymaking, from manifest destiny to slavery, women’s suffrage, civil rights, and immigration. In the area of science, public policy smear and disinformation campaigns have taken place over issues like DDT, tobacco, acid rain, the earth’s ozone layer, clean air and water, climate change, and COVID vaccines (Oreskes 2011). Anti-democratic dynamics in policymaking tax our time and patience, harden our positions, deepen our distrust in facts and government, and delay solutions to important problems. They can even lead us to adopting the wrong policies altogether.

What does any of this have to do with open access? Open access is a term that has gained much attention in research communication circles over the last twenty years. Generally speaking, it means making information easier to find and share, including but not limited to research information. Countries around the world have focused on open solutions reforms (including but not limited to open access, open data, open educational resources, and more; see Hampson 2021) as being essential to the future of research. The reason for this is not entirely clear, although effective advocacy and constant publicity about publisher profit margins has elevated open access into a sort of cause celebre, with OA advocates being heroic Robin Hoods stealing from the rich and giving to the poor. Our passions appear to have inflamed OA reform ideas into being proxies for reforming the future of research. There is no actual international effort for this kind of work, of course (see Box 1), so open access policies, and to a lesser degree open science and open data policies, have become global research reform policies writ large, soaking up policymakers’ attention and creating changes that affect a broad swath of research and research communication practices well beyond just making information more open. In this open solutions race, open access policymakers have so far created the most policies with the most wide-ranging impacts on research.

Unfortunately, the evidence our policymakers have been relying on is inadequate, and the seriousness of our deliberations has not been commensurate with the significance of the policies in question. Our debates have instead been swirling in an anti-democratic eddy for decades, during which time we have not carefully listened to all parties involved—despite what in many cases are genuine efforts to listen and learn—and have instead allowed the policymaking process to be guided more by the opinions of interest groups and biases of policymakers than by objective facts and evidence. This pattern is, maybe unsurprisingly, consistent with the policymaking biases we have seen for many other high-profile science-related issues over the years. As a result, some people view the open access regulations we have created today as a significant and noble accomplishment while others see them as a complete failure unworthy of science. Is there a path toward open access policymaking that is more democratic and evidence-based? And if so, is it even possible to backtrack and think about new policy frameworks?

BOX 1: GLOBAL PUBLIC POLICY DEVELOPMENT IN RESEARCH COMMUNICATION

In democratic socieites, our ideal is for policymaking bodies to operate within their own spheres of influence and expertise. We neither want nor expect our local health department to design electrical codes, or the US to design immigration laws for France. We also expect strong communication in the policymaking process between those who design policies and those who will be affected. If there is too much disconnect between policy makers and the governed, we end up with unreasonable, unjust, ineffective, and unsustainable laws. Ultimately, of course, public policy is going to be influenced by external factors like bias and politics. But to the extent possible, democratic societies always aspire to the ideal that policymaking is driven by expertise and evidence, and works for the greater good; it should not be ideological driven, or inflict harm on society (although, of course, much of it has throughout history).

When it comes to developing research communication policy, who is the expert? No one really. There are enormous scholarly societies like the American Association for the Advancement of Science and American Geophysical Union who have participated in high level conversations on research communication topics for decades. Similarly, research institutions like the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Max Planck Institute and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory all have decades of experience thinking and publishing insights about these issues. Government agencies around the world have also been deeply engaged, from the US National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, and National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine, to China’s Association for Science and Technology, Brazil’s São Paulo Research Foundation, India’s Ministry of Science and Technology, UK Research & Innovation, Horizon Europe, the Autralian Research Council, and many more. All have hosted and participated in conferences about issues in research communication for years. Publishers have also participated and helped fund these conversations, along with universities, llibraries, philanthropies, and interest groups. The collective expertise of these groups regarding research communication policy is deep, but it is also disbursed throughout the world.

When it comes to creating global research policy, then, which single agency has the standing and expertise to do so? Here again, the answer is no one. There is no single voice that speaks for all research everywhere. The needs, perspectives, priorities, practices, and unique knowledge are far too widely disbursed. Added to this, creating a single policy for all research everywhere is akin to developing a single policy for all sports—saying that henceforth, all athletic contests shall involve a ball weighing 450 grams on a field measuring 50 by 100 meters. This kind of policy might be okay for soccer, but the impact on basketball would be interesting and the impact on swimming would be nonsensical. Even if we do hear from all voices and then attempt to create a single policy that averages out everyone’s ideas and concerns, the resulting policy still wouldn’t necessarily make sense in this case.

At the international level, certain agencies have been given the authority by the international community to develop global policies covering a range of issues, from human rights (UN OHCHR) to international monetary policy (IMF), economic development (IBRD), copyright (WIPO), health (WHO) and climate change (IPCC). UNESCO is the only international agency vested with the authority to develop science policy. Although it doesn’t have a team of dedicated science policy experts on staff, or a large team of scientists (which arguably makes it an unusual candidate for this job*) UNESCO does have a mandate to be “a laboratory of ideas,” and attempt to offer “a broad range of expertise in the fields of Education, the Sciences and Culture” (see unesco.org). In service to its mission, UNESCO does amazing work, attempting to assemble international teams of individuals and organizations to research and consult on various policies.

It was with such commitment and vigor that UNESCO attempted in 2019 and 2020 to hear from the entire global research communication community and then craft a policy that fairly and accurately reflected the needs and perspectives of researchers from around the globe with regard to open science reforms. Some have hailed this effort as an historic success; others (including OSI) have noted that the final policy misses the broader point that one-size-fits-all approaches can’t work in research. In terms of effort, however, UNESCO’s final product—the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science (see UNESCO 2021)—stands far above Plan S and the Nelson Memo in terms of commitment to our democratic public policy ideals, since both of these major policies involved no consultations of note with researchers or research communication groups. What’s doubly unfortunate is that even though both of these policies were ostensibly designed to only affect a subset of researchers within the borders of the EU and US, their impact is becoming global (Plan S, having a three-year head start on the Nelson Memo, is having the most impact at the moment). Plan S in particular, with its focus on the expensive article publishing charge method of paying for research publishing, is exacerbating existing global inequities in research due to a mismatch between the needs and resources of EU researchers and the needs and resources of the Global South (e.g., see Mwangi 2021 for a discussion of resource constraints in Kenya).

Is there another way to reform global research communication policy? More inclusive, evidence based policies would be a good start, particularly to the degree that researchers themselves can be more involved in policy discussions and development. See the policy options discussion section later in this report for more detail.

*Contrast this with the World Bank (IBRD), for example, which is tasked with global economic investment and development but is staffed by thousands of economists and development specialists from 189 countries around the world and has field offices in 130 locations to keep close to projects and development issues. Similarly, WIPO has hundreds of patent attorneys, WHO’s team of 8000 professionals includes many of the world’s leading public health experts, including doctors, epidemiologists, scientists and managers, and the IPCC consists of the world’s top climate experts and support staff.

AGREEING ON DEFINITIONS

A first step might be to agree what open access even means. As mentioned above, this term generally means making information easier to find and share. At its core, this means free to read. But the exact definition involves lots of caveats, depending on who is doing the defining. Some say information is only open access if it is free to read plus licensed in a way that permits unlimited reuse with attribution (a CC-BY license). Others say free plus CC-BY is not sufficient, and that additional conditions are also necessary, like zero embargo (no delay between publishing and accessibility). Still others pile on even more conditions like metadata, repository requirements, and data sharing. The same caveats are true for open data, open code, open educational resources, and more, where different kinds of information have different kinds of open definitions, conventions, options and outcomes.

In this report, we will use the terms open and open access interchangeably (along with the term open solutions, which is a blanket term describing all open approaches). This overlap is intentional. The world outside the confines of scholarly communication experts has conflated these terms and used them interchangeably, so much so that trying to make a distinction between them is now more confusing than helpful. At least in the policymaking world, OA and open now mean the same thing.

UNDERSTANDING HISTORY

Over the past 20 years, many valiant open access scholars have tried to organize the different ways in which “openness” is described.2 Their efforts have ventured beyond just defining open, and have instead focused on trying to understand why we speak with so many different languages when it comes to our open goals and methods. These scholars have invented a multitude of plausible explanations, all correct to some degree, including noting that many different philosophical motivational, epistemological and economic motivations exist for open. But how did all these differences arise in the first place? The economic explanation may be correct one to adopt (Mirowski 2018), but there’s also a simpler explanation. As it turns out, the concept and practice of openness has been evolving along at least half-dozen distinct historical paths over a very long time, in some cases for centuries already. Over the years, these histories have led to the formation of entirely different branches of open, each with its own completely and legitimately different ideas about what open research looks like and how it should grow in the future.

The first historical branch of openness comes from within research itself. The need to share ideas and discoveries has always been a bedrock principle of scientific investigation (Poskett 2022). Over time, researchers have been adept at inventing the solutions they need (and that work) to communicate more openly and effectively with each other, including forming new scientific societies; attending conferences; creating new journals; creating a multitude of data catalogues and indexes; creating new standards; creating binding guidelines on the social and ethical need to share research data (see Box 2, for example); and creating highly successful data sharing and research collaboration partnerships and networks, particularly in the life sciences, high energy physics, astronomy, and genetics.

A closely-related second branch of OA evolution centers around publishing practices. Research and the dissemination of research findings have always been closely tied.3 Widespread use of the printing press started around the late 1500s and was a transformative event in human history that fundamentally changed our expectations for how knowledge could and should be shared (see Johns 1998), particularly for the practice of systematized research, which was just beginning to take root. By the mid-1800s, publications established explicitly to share ideas and discoveries were proliferating—over 1300 journals now existed. It was crucial for scientists to be aware of what knowledge already existed in their field, but even then, doing so was becoming increasingly difficult. This need for more openness and increased awareness gradually led to standards and systems for what constituted clear and rapid sharing of knowledge, claims to discovery, proper citation methods and more (Csiszar 2018). These standards and systems have continued to evolve today in response to the ever increasing growth of research, in response to the ever changing needs of researchers, libraries, funders and governments, and in response to the huge market opportunities available for creating the best new systems.

BOX 2: A VERY ABBREVIATED HISTORY OF HOW WE SHARE HEALTH AND MEDICAL RESEARCH

Organized information sharing in health and medicine has existed in every society around the world and every epoch of history long before open access policies, computers or the Internet. Public health efforts have been a major driver of this need, typically focusing on priorities like malnutrition, infection, and sanitation. This vital knowldge was documented, taught, preserved, shared and improved upon across regions and genarations (see Tulchinsky 2014 for a brief but rich overview). Over time, as the world became more connected through travel and trade, formal international health collaboration resources and organizations began to emerge. In 1892, for example, the International Sanitary Convention was formed to help control cholera. Following World War II, the newly-established United Nations created the World Health Organization, which began sharing information on malaria, tuberculosis, venereal diseases, maternal and child health, sanitary engineering, and nutrition (McCarthy 2002). By the 1960s and into modern times, information sharing across health and medicine was commonplace, highly valued and strongly encouraged (Fienberg 1985). This is a comically short recap of history; our point here is only to highlight, in this box, that information sharing in these fields is nothing new.

The rules and conventions governing how health and medical information is shared, as well as the conduct of medical research itself, largely evolved in an ethical vacuum until the mid-20th Century (there were codes like the Hipocratic Oath, but these were often incomplete or horribly biased). The first major modern rule on research ethics was the 1949 Nuremburg Code, written to ensure that Nazi crimes committed during the Holocaust would not occur again within the medical profession. The Nuremberg Code established that the informed and voluntary consent of research subjects was essential to any research trial; that proposed research must benefit society; that any proposed research study must safeguard the well-being of its subjects; and that the risks of any study must be calculated and justified. Most importantly, the Nuremberg Code imbued medical research with a responsibility to human dignity and human rights. This responsibility was expanded fifteen years later in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, issued by the World Medical Association, which not only reaffirmed the Nuremburg Code’s ideals, but also established that underrepresented peoples should be given access to studies and study results. Fifteen years after Helsinki, the Belmont Report of 1979 (issued by the US National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research) introduced the importance of using justice and fairness as guiding principles in medical ethics. The report also espoused that when research is supported by public funds, those who take the risk (i.e., the tax-paying public) must experience the advantages, not just those who can afford to access the data.

Many detailed polices governing how and why to share medical research have since been constructed on these ethical frameworks. In 1982, 1993, and 2002 the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) issued a series of guidelines for clinical trials research, followed by similar guidelines from several other organizations during the 1990s and early 2000s (such as CONSORT for clinical trials data). Numerous medical privacy laws have also emerged, along with sophisticated policies and safeguards at the clinic and hospital level. Over the past 20 years in particular, governments and life sciences funders around the world have increasingly merged these old and new information sharing requirements—pushed for the most part by increasingly complex array of funding and regulatory requirements, and recalling that information sharing has always been done (it’s mostly just the tools that are new)—with the ethical guidelines and imperatives for sharing data envisioned by Helsinki and Belmont. These resulting new guidelines are robust and expansive, establishing that researchers have a responsibility to protect not only patients and society, but research itself. Modern guidelines include strict compliance with complex clinical research protocols (often hundreds of pages long), clear transparency, proven lack of conflict, proven benefit, demonstrated replicability, advanced scientific and statistical rigor, robust data sharing plans, and more—every attribute of high quality and socially responsible research. Layers of regulatory review and approval by government and/or funding agencies are involved, plus alignment with patient privacy protection laws like HIPPA and GDPR, and oversight by and accountability to institutional review boards, scientific advisory boards, data safety monitoring boards, community advisory boards, and more. And in this midst, a seeming infinte array of research collaboration programs and data sharing networks have evolved, all successfully abiding by their own sharing rules and requirements that supplement this new ethical sharing framework.

Until very recently, none of this history has had anything whatsoever to do with open access, open data or open science. Rather, history has simply unfolded organically over time with input from researchers in order to meet the ethical obligations of research and ensure that research is done right.

A philosophical offshoot of this second branch, technically distinct enough to be considered a third branch, is the growth of computer technology and the Internet starting around the mid-1980s. Once again, as with the advent of printing, these developments fundamentally changed our expectations about access to information, and paved the way for more open developments in research and society, such as the launch of GenBank in 1992 by the US Los Alamos National Laboratory, the world’s first public access repository of nucleotide sequences; creation of the world’s first preprint server, arXiv, in 1991 (originally for physics and astronomy research); publishing of the world’s first OA journals (through SciELO in 1997); formation of the Open Source Initiative in 1998 to help govern computer code; the world’s first OA megajournal (PLOS in 2000); and development of the first open educational resources (by the Hewlett Foundation in 2001). Today, it’s impossible to underestimate the influence that technology and the Internet have had on all things communication, from rapid download speeds to social media to the proliferation of publishing platforms. These developments continue to raise our expectations and increase the potential for what communication can become, not just in research but across society.

The fourth distinct branch in the evolution of open knowledge has centered around social development. Over time, the slow and steady march of the scientific method—valuing evidence, openness, transparency, accountability, and replicability—and its success at unlocking true knowledge has influenced everything from philosophy to politics, law and industry, which in turn has created more “norming” of this approach, particularly in the West.4 For example, not long after the start of the Scientific Revolution in Europe, when natural philosophers such as Copernicus and Galileo successfully challenged prevailing explanations for how the world worked (as defined by Aristotle and the Catholic Church), social philosophers such as Locke, Hobbes and Rousseau (among others) were inspired to start questioning the world’s social order. This work led directly to revolutionary new political concepts, including France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man, and the US Constitution (both passed in 1789), which employed the Scientific Revolution’s spark that even man and society were tied to the natural world through natural rights.

In parallel with this growing appreciation of and our need for the scientific method, science and technology became driving forces of global development in the 1800s, with breakthroughs in physics, medicine and biology igniting massive change throughout the world. The public’s thirst for knowledge and enthusiasm for learning more about the natural world became a global phenomenon that continued into the first decades of the 1900s. By the aftermath of World War II, Karl Popper’s “Open Society and It’s Enemies” made the case that the open knowledge ethos of science needed to spread beyond science and into the fabric of societies—that it was important now more than ever to construct societies where truth is widespread and easily accessible, lest we backslide again into a world ruled by totalitarianism and fascism.

Popper’s work is generally acknowledged as the formal intellectual beginning of the open society movement. Today, many open advocacy groups travel along an offshoot of this branch, characterizing the need for open science as a social justice issue. The massive technological influence of the Internet has both influenced and enabled this ongoing work and development, raising our expectations for what technology can do for open knowledge and open society, and enabling this change, which in turn has lead to higher expectations and even more change.

A fifth historical branch of open has been accountability. Before the mid-1950s, accountability in research was largely internal, focused on ensuring that research was accurate, and that systems for reporting and writing about research were broadly accepted. In the post-WWII era, as government spending on research increased dramatically, the need for greater public accountability in research also developed, both financially and in terms of public access to what we were spending money on and why. Systems of accountability have now evolved to sophisticated heights, from grant evaluation procedures to modern research impact evaluation procedures and freedom of information laws, all from different government agencies and with different objectives. For example, the world’s first nationwide open access policy for scientific research was implemented by the US National Institutes of Health in 2008 (Suber 2008). What we now recognize as peer review was born out of US Congressional oversight into research in the mid-1970s (Baldwin 2018). And many countries now have their own research impact evaluation systems, perhaps none more carefully designed than the UK’s Research Evaluation Framework (REF 2021).

A SIXTH BRANCH EMERGES

Amidst this centuries-long evolution of open thought and practices, participants at a 2002 conference in Budapest (the Budapest Open Access Initiative, or BOAI) advanced the idea that open access meant only one thing: that in addition to being free, research also needed to be licensed in a way that optimized the potential for its unrestricted reuse, free of its typical copyright restrictions. The goals were simple: by making information free and easier to access and reuse, we could democratize research, lower publishing costs (by untethering publishing from publishers), and better serve the public good.

The language used in the BOAI declaration was lofty and Panglossian, reflecting the vision of the Internet circa 2002 that we were on the cusp of a world where information would soon flow freely across borders with little cost and enormous benefit for all mankind. Adding fuel to this declaration, several of the BOAI signatories would in the coming decade become the most prolific, eloquent and vocal opponents of high profits in commercial science publishing, including Steve Harnad, Leslie Chan, Jean Claude Guedon, Peter Suber, Michael Eisen, two representatives from the Open Society Institute, and one representative from SPARC (the Scholarly Publishing and Academic Resources Coalition; SPARC in particular would lead the anti-publisher march over the next 10-15 years).

Subsequent modifications to BOAI made at conferences in Berlin and Bethesda stipulated that research also needed to be made immediately available, with no delay allowed between publishing and free access to the public.

THE SIXTH BRANCH BECOMES ALL WE NOTICE

Over the next decade, promoted by the effective voices who helped craft this statement, supported by the money and organizing acumen of SPARC and the Open Society Institute,5 and made timely by the spiraling cost of journals for academic libraries where, prophetically, commercial publishers played the role of the boogeyman to perfection,6 the BOAI approach to open access became the bedrock philosophical foundation for most subsequent open access policies, and it continues to be so even today. All other historical branches of open access have been ignored.

This isn’t to say that BOAI’s policy recommendations were wrong. To many believers, they were exactly on target. Rather, the most vocal post-BOAI open advocates tended to portray open access as a contest between good and evil. Policy debates became urgent, polarized and confrontational—even personal. The policy space became a battlefield where there was no middle ground, and no willingness to understand issues from all sides, ignoring the different histories involved and the differing needs and points of view centuries in the making. Ideology was not only trumping the expert-driven democratic policymaking ideal, it was beating it into the ground with a hammer of righteous might (see Box 3 and Plutchak 2022). As one research leader remarked on the OSI listserv in 2018, we were going about reforming science in a very unscientific manner.

BOX 3: THE GOOD VERSUS EVIL APPROACH TO OPEN ACCESS POLICYMAKING

The open access debate is more civilized today than it was during its heyday—roughly the 15 years between 2003 and 2018. In the words of T Scott Plutchak, describing the legislative and political efforts of the Scholarly Publishing Roundtable between 2009 and 2012—work that eventually led to the 2013 Holdren Memo’s expansion of the US Public Access program—“One of the paralysing results of [the] pitched battle [between opposing camps at this time] was that individuals who might have been allies in other circumstances found themselves on the opposite sides of a very public rhetorical war” (Plutchak 2022). Still, although the public rhetoric may have died down, very strong differences of opinion remain. For example, to some in the open access community, publishers are not legitimate parts of the research ecosystem at all, but parasites who feed on it. This opinion is even reflected in the language of several major open access policy statements in use today, and factors into the philosophy of several leading groups in the open access funding world. In a sense, what open access policymakers are being influenced by is more than just the facts and evidence about open access, but by a belief that the effort to develop open access policies is a battle between good and evil. This is not an outlier opinion; even some in OSI support this philosophy and policymaking approach. From a democratic and evidence based policymaking perspective, however, these opinions make it difficult to focus on and be led by facts. Rather than working together to help researchers improve research communication based on their needs and perspectives, the good versus evil approach puts a thumb on our scale of objectivity.

CASE 1: SCI-HUB

The pirate publisher Sci-Hub probably best exemplifies the good versus evil approach. Created in 2011, Sci-Hub has used stolen and donated university credentials and other hacking methods to download nearly 90 million copyrighted books and journal articles from research publishers, which it then distributes for free through the Sci-Hub website. Publishers have successfully filed numerous copyright infringement injunctions against Sci-Hub but the site keeps moving to new internet service providers and therefore keeps operating. Many researchers around the world see Sci-Hub’s work as heroic; and even though many universities block the site, researchers around the world use it anyway because it fills an important need. Estimates vary but more than 50 million articles per month are downloaded from this site (Owens 2022). Justifying its actions on the Sci-Hub home page and even soliciting funds for its legal defense, the website states “The position of Sci-Hub is: the project is legal, while restricting access to information and knowledge is not. The current operation of academic publishing industry is massive violation of human rights” (Sci-Hub 2023).

CASE 2: PLAN S

The EU’s Plan S is transforming the world of scholarly publishing. The plan’s coordinating body is cOAlition S. As stated on the cOAlistion S website, “Publication paywalls are withholding a substantial amount of research results from a large fraction of the scientific community and from society as a whole. This constitutes an absolute anomaly, which hinders the scientific enterprise in its very foundations and hampers its uptake by society….[Our] collective duty of care is for the science system as a whole, and researchers must realise that they are doing a gross disservice to the institution of science if they continue to report their outcomes in publications that will be locked behind paywalls…. There is no valid reason to maintain any kind of subscription-based business model for scientific publishing in the digital world, where Open Access dissemination is maximising the impact, visibility, and efficiency of the whole research process” (Coalition-S 2023).

CASE 3: CHARITABLE FOUNDATIONS

Charitable foundations like Gates, Mellon, and Arcadia are major players in open access reform, leading and contributing heavily to open access policy reform efforts around the world. For several of these foundations, their work is fueled by the philosophy that our current system of scholarly communication is unjust. These groups are not necessarily wrong, of course, nor are they required to act objectively like government policymaking bodies, but the influence of these groups in the open access space has been significant, and has created so much policymaking overlap between advocacy channels and official policy channels that it’s difficult to tell where ideology ends and objectivity begins. On the Arcadia Fund’s website, we read that “Access to knowledge is a fundamental human right. It advances research and innovation, improves decision-making, exposes misinformation and is vital to achieving greater equality and justice. The internet has transformed how we share, find and use information. But some materials that should legally and morally be free for anyone to access are still constrained by paywalls and restrictive copyright regimes…. Restrictive copyright laws are a significant barrier to open access. They benefit few, while denying many access to vital knowledge. We support efforts to challenge and improve existing laws, regulations, exceptions and limitations so that people have better access to knowledge they need” (Arcadia Fund 2023).

Today—and despite a large, meaningful and influential array of open tools, policies and efforts, from the Panton Principles and FAIR Principles governing open data (2009 and 2016 respectively) to a thick alphabet soup of important organizations and principles (DORA, GitHub, OSF, Lindau, PubMedCentral, et al)7— the BOAI approach has become an article of faith for most of the world’s significant open access policies,8 from Europe’s Plan S to UNESCO’s open science policy to the University of California’s transformative agreement with Elsevier and the new US open access policy (the Nelson Memo).

The idea that open means free, immediate and licensed for unlimited reuse is not challenged. Most major funders have also fully accepted this approach to open access.9

As our global open access policymaking efforts move forward, it’s important to remember there are many histories and forces still influencing open practices. Understanding this will help us better understand what needs to be done and where we might want to concentrate our efforts for maximum effect and sustainability. In this policy space, there is a tangle of history, actors, needs, motives, and objectives. We may want “open” to be a simple notion with a straightforward past and an obvious future, but as we shall continue to explore in this report, it is none of these things.

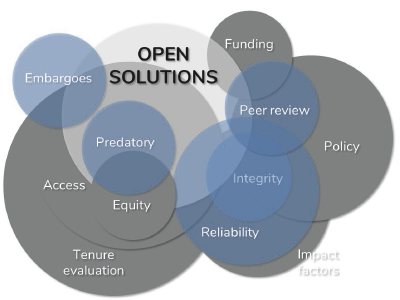

OSI

The Open Scholarship Initiative (OSI) was founded in late 2014 to listen to all sides in this debate, lower the temperature of the discourse, broaden understanding of various perspectives, and develop fact-based approaches to open access policy. There have been many other multi-stakeholder conversations happening as well, such as FORCE11, the Research Data Alliance (RDA), the Committee on Data of the International Council for Science (CODATA), and the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA). OSI’s unique value proposition has been to bring together high-level representatives from all key stakeholder groups and organizations and have them work directly together to find common ground on key issues in scholarly communication—not just open access, but tangential issues like impact factors, peer review and the culture of communication in academia. An important part of our mandate has also been to represent and protect the interests of all countries in this conversation, not just focus on what works for the EU and US.

Where does OSI stand on current OA policies? As noted in our 2020 Common Ground paper (Hampson 2020) it’s fair to say most participants in OSI agree that (1) Research and society will benefit from open done right; (2) Successful solutions will require global and inclusive collaboration, (3) Connected issues (like peer review and impact factors) need to be addressed, and (4) Open isn’t a single outcome, but a spectrum of outcomes.10 Beyond this, OSI participants have a wide variety of opinions, and our role isn’t to speak with one voice. There are some in OSI who are thrilled with these policies, and others who aren’t. It’s also probably fair to say that amongst the analyst community—and this is the community which has been most active in OSI conversations over the years—there has a been a considerable amount of discussion regarding the pros and cons of various policy approaches, and a general understanding that we need to be on the lookout for unintended consequences.

Probably the most impactful transformation happening today involves flipping the subscription model for scholarly publishing to a model where authors pay for publishing via article publishing charges (APCs). The APC model is mandated by Plan S, covering a large portion of the EU (even though this affects a small global portion of publishing, publishers have been transitioning to Plan S requirements for years now), and is strongly directed by the new Nelson Memo covering all federally-funded US research (which will give a huge new push to the transition).11 The general idea is that authors can simply tap their research budgets to pay for publishing, and in exchange the publisher will get paid and make the article free to read.12

There are many other transformations happening as well, of course, such as eliminating embargo periods, requiring a CC-BY license on all work in all disciplines, improving data availability, negotiated agreements at major universities whereby access to published work and APC charges are bundled together, and more, It is unfortunately well beyond the scope of this paper to dive into each of these policy prescriptions at length. For our purposes here, many in the OSI community have expressed four general concerns about the overall nature of these reforms: (1) ignoring the unintended consequences of APCs; (2) ignoring the evidence that in practice, openness exists along a broad spectrum of outcomes; (3) our tendency to overreach and design policies for which we lack the requisite expertise; and (4) forcing one-size-fits-all open solutions on researchers, even where these solutions don’t match researcher needs and resources.13 The following subsections describe each of these concerns in more detail.

THE UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES OF APCs

The APC-funded approach to open (which is central to policies like Plan S) is not free. Indeed, APC charges have risen to stratospheric levels for premium research journals over the last few years, now topping US$10,000 per article for publishing in top research journals. Even the average APC charge (around US$2600 for OA mirror journals, although there is wide variation by field, publisher, and journal quality; see Smith 2022) is now far higher than most researchers around the world can afford unless they are based at a major institution in the US or EU or are well endowed by their private funder.14

As noted is OSI’s official critique of Plan S, many worry that our widespread use of APCs will widen the chasm between the haves and have nots in research, and substitute one equity imbalance with another: the inability to pay for access (paywalls) due to high subscription costs, with the inability to publish (playwalls) due to high APCs. Since this chasm roughly equates to a fracturing of the open access policy space along economic and regional boundaries, the US and EU will have their own rich open universe, other parts of the world will have their less endowed universe, and the gaps between these worlds may end up hurting research instead of helping it (for many reasons: technical difficulties with sharing, cost differences, protectionism, less collaboration, and more).

The APC approach to open access also doesn’t reduce the power of major commercial publishers to the degree BOAI and other OA ideologies originally intended. The power of major commercial publishers is increasing instead, because the APC model is proving to be quite financially robust (Pollock 2021 and Zhang 2022) and because society and university publishers need help navigating the rapidly changing regulatory landscape.15

This power will probably continue to grow in the coming years as publishers lock in their consolidation by offering value added tools to their customers (like advanced search and synthesis). Rich countries and institutions who can afford to climb the ladder of publisher-controlled offerings will partake in a buffet of new capabilities made possible by more open access, while lower income institutions and countries will have to make do with the bare minimum Author Accepted Manuscripts and Excel spreadsheets mandated by open policies. There is no money or incentive to make this kind of advanced access available for everyone everywhere. Rather, everyone will be required to contribute their information for free, and only the rich will be able to extract maximum value from it.

THE BROAD SPECTRUM OF OPEN OUTCOMES

As discussed, our most influential open access policies are not, unlike actual public policy, grounded in a wealth of evidence, nor have they been developed through the expert and impartial consultative process we expect to see in democratic societies. Instead, they are ideologically grounded. This ideological approach makes sense to those who consider the act of locking research behind subscription paywalls to be an inherently immoral act. For this group, trying to put commercial publishers out of business is a morally justified imperative. But not everyone feels this way. In practice, open access efforts are driven by a variety of motives such as the desire to improve impact, efficiency, reproducibility, accountability, transparency, and collaboration. Many researchers also readily appreciate that publishing adds value to the research record through processes like gatekeeping, peer review and preservation, and note that without a reliable process akin to quality journals, the scientific record may become unreliable.

This difference between ideology and evidence is also apparent when it comes to defining what open means. Ideology says that open is, at minimum, CC-BY licensed information without embargo, but evidence clearly shows open comes in many different forms and looks different for different users in different fields and different parts of the world. OSI participants developed an information model called “DARTS” to describe this open spectrum, where the five letters of this acronym stand for discoverability, accessibility, reusability, transparency, and sustainability. On this spectrum, we allow for the fact that some kinds of open are free to read but still copyrighted; other kinds may be closed to the public but robustly open and interoperable within designated user groups (this solution is common in clinical research); and still other kinds are public domain licensed but not very discoverable, transparent or sustainable. So-called “green” open, which accounts for the vast majority of open resources, is exactly this: a hodge-podge of information that is free to read but whose discoverability, accessibility, reusability, transparency and sustainability vary widely. This diversity reflects the fact that different user groups have different resources, needs, incentives, motives, conventions, restrictions, and so on. It doesn’t mean they shouldn’t strive to improve their openness, but it also doesn’t presuppose that one type of open is necessarily superior for all users and circumstances. Movement toward better open solutions should continue, but this movement should be based on evidence and need, not assumptions.

FIGURE 1: OSI’S DARTS OPEN SPECTRUM

DISCOVERABLE: Can this information be found online? Is it indexed by search engines and databases, and hosted on servers open to the public? Does it contain adequate identifiers (such as DOIs)?

ACCESSIBLE: Once discovered, can this information be read by anyone? Is it available free of charge? Is it available in a timely, complete, and easy-to-acceess manner (for instance, is it downloadable or machine-readable, with a dataset included)?

REUSABLE: Can this information be modified? Disseminated? What conditions (both legal and technical) prevent it from being repurposed or shared at will?

TRANSPARENT: What do we know about the provenance of this information? Is it peer reviewed? Do we know the funding source (are conflicts of interested identified)? What do we know about the study design and analysis?

SUSTAINABLE: Is the open solution for this information artifact sustainable? This may be hard to know—the sustainability of larger, more established solutions may evoke more confidence than new, small, or one-off solutions.

The DARTS framework is currently only a concept and not a measuring tool, although quantifying this tool might help make it useful to open research in other ways. For example, imagine running a scale from let to right, and then assigning a value for each DARTS attribute of a paraticular information artifact. Assignng a transparency score of zero means we know nothing about where this information came from, whereas a nine means we are very clear about this. Doing the same for each DARTS attribute, we could then assign a perfectly open object a DARTS score of 99999, and an absolutely closed object a score of 00000. Almost all information exists somewhere in between. This paper, for example, will have good discoverability and accessibility (although not as good as a commercially published report), limited reusability, acceptable transparency, and good faith sustainability (although not perfect, like commercial publishers). Therefore, its DARTS score might be 77586 or some such.

Indeed, after 20 years of pushing for ideologically perfect open solutions, most of the world’s open information is still published in other formats (which isn’t to say closed, just imperfectly open). Estimating the exact distributions of open outcomes depends on which indexes are analyzed (different indexes skew toward different journal types and disciplines), which regions of the world are being measured, and the sampling methodology used (see Box 4), but according to a recent analysis of eight million journal articles listed in the Web of Science between 2015 and 2019, BOAI-compliant articles (for which Gold OA is a rough proxy) account for only a small fraction of the total (Table 1 and Simard 2022). What researchers want and need for open information, then, isn’t necessarily always the same as what’s being prescribed. Open access policy may require one outcome, but evidence shows many different outcomes are possible, even preferred.

TABLE 1: PERCENTAGE OF OA PUBLICATIONS BY TYPE AND FIELDS (2015–2019)

| Field | Total OA | Of which Gold* | Of which Green |

| Natural Sciences | 45.4 | 19.9 | 36.3 |

| Engineering and Technology | 30.4 | 13.0 | 21.4 |

| Medical and Health Sciences | 50.0 | 20.8 | 40.4 |

| Agricultural Sciences | 35.9 | 17.1 | 22.0 |

| Social Sciences | 35.5 | 7.9 | 29.8 |

| Humanities | 21.2 | 5.9 | 15.8 |

| Unknown | 35.8 | 2.2 | 31.3 |

| All Fields | 42.9 | 18.1 | 33.8 |

Source: Simard 2022.

*Gold OA represents open access materials which have been made open through APC charges and made immediately and freely available to the public without embargo. It does not necessarily mean the materials are CC-BY licensed, however. DeltaThink estimates that of all the open materials currently being published during this same time period (2015-2019), about 55% in aggregate was CC-BY licensed, meaning that only about 10% all published materials (55% of 18.1%) are strictly BOAI-compliant. See Pollock 2022. This figure is consistent with other global estimates of gold open (see, for example, Zhang 2022 and Piwowar 2019).

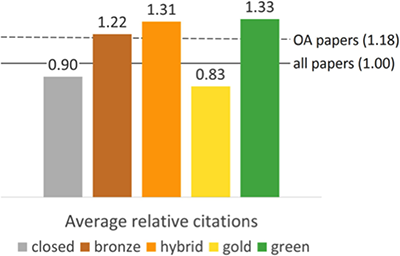

How can we know for sure which of these outcomes are best? We can’t—we need more research, without which our policy conversations have been stymied and our positions hardened along ideological lines. This need for more research isn’t a red herring argument like the tobacco industry used in the 1970s and 80s to slow down anti-smoking policy. In truth, as a community we have conducted almost no solid research into fundamental questions, such as which researchers need open and why, what types of open work best in each field, how short embargo periods can go, the cost-benefit of replacing the subscription model, the open access citation advantage (see Box 8), and more.16

BOX 4: WHOSE EVIDENCE?

Scholarly communication research isn’t an exact science. Researchers will typically investigate open access in unique ways from one study to the next, segregating their findings into different types of open that aren’t necessarily comparable, or using the same category names like green and gold but defining these categories in slightly different ways, or sampling data from different publication indexes, over different time periods, focusing on different fields and countries, or using different sampling methodologies. As a result, these studies always arrive at different conclusions, often markedly so, about how fast open access is growing.*

Some of the most methodologically refined analyses to-date have taken measurements across multiple indexes, regions, fields and time periods (like Piwowar 2018 and Archambault 2016), but even here, the aggregate data from these studies may be less meaningful than accurately understanding whether a particular field or country is currently making progress toward its open goals. And across all studies, none to our knowledge have fully captured the breadth and depth of green open, which is defined in a variety of ways by researchers but should arguably include all research-related information that is free to read and not clearly gold or bronze, from preprints to self-archived reports on university websites, to datasets available in repositories (and not otherwise CC-BY or CC-0), to most of the information in massive archives like PubMed Central, and copyrighted work that is now free to read everywhere, not just academic journal articles in OA repositories (see, for example, the wealth of infomation being catalogued by coherentdigital.net).

This inconsistency and variation is important to understand for two reasons. First, because our analyses can vary so widely, OA policymakers can be tempted to use hand-picked statiscs that support their favorite OA story line, such as rapid growth rates for their preferred form of open. This bias is not unusual in policymaking, of course, but we can help give policymakers a more solid foundation of evidence by firming up our research methods. Second, only two types of open are deemed ”acceptable” by most of the world’s major OA policies: gold and diamond.** Thefore, it’s important to develop a better understanding of how these forms of open are actually faring, particularly with respect to their historic growth trends and to other forms of open. As noted in Table 1 and Figure 1, the marketplace has a wide variety of open outcomes.

How do we know which of these outcomes is working best for researchers? We don’t. Many studies over the years have tried to measure the growth of open solutions, but there haven’t been any studies to-date (to our knowledge) that investigate which of these different solutions are the ones actually preferred by researchers. We do know from surveys (see, for example, Hampson 2023) that the APC solution is widely disliked, so we can infer from this that gold open is not an outcome most researchers look upon fondly (at least in aggregate) if given a choice. Some researchers also don’t like the idea of paying to publish their work, and others feel that pay-to-publish journals are lower quality, or have lower reputations or lower readership. University tenure committees typically feel the same way, although this attitude is gradually changing. These factors might help explain why gold open has been stuck at below 20% of all open outcomes (and only around 5-10% of all published work; see OSI 2021) for the last 20 years.

Gold open will surely grow in the coming years, though, due to the influence of Plan S and the Nelson Memo, piled atop current growth trends (Piwowar 2019). This isn’t necessarily a bad development if the issue of APCs can be resolved. But given historical growth trends, it may be helpful to gather more evidence about what researchers actually want and need from open publishing solutions so we can make sure we focus on growing the right kinds of solutions. To-date, we can only tell that the marketplace is producing a wide variety of outcomes, and that most of these outcomes are not the ones OA policymakers want (at least yet). A first step in this process might be to fund more carefully designed and definitive studies that can give us a clearer picture of the open environment so policymakers can develop better evidence-based policies moving forward.

*For example, older, higher-impact, STM-centric work will be listed in indexes like Scopus and WOS (Web of Science). Measuring the open content in these indexes (as in Simard 2022) will tend to show slightly lower growth. Newer journals are more likely to be picked up by newer indexes like Unpaywall, which detects the DOI of journal articles (older articles are less likely to have been assigned a DOI). Measurements done from this index (like Piwowar 2019) will tend to show higher growth.

**Gold open is where the final version of record of an academic journal article is made freely and immediately available for the public to read and reuse through author publishing charges (APCs), which are often (but not always) paid by the author, the author’s grant funds, or the author’s library or institution. Diamond or platinum open, which are far less common than gold but still acceptable to Plan S, are variations on this theme where fewer or no author charges occur. In these cases, publishing is managed and subsidized by a research community, academic community, or nonprofit and no publishing charges are drawn from the author’s pocket, grant funds, or research institution.

What we can clearly see from a number of researcher surveys over the years17 is that at minimum, getting free and immediate access to journal articles isn’t the only concern researchers have. Researcher also want lower publishing costs, improved connections with colleagues, and increased visibility and impact for their research work. This isn’t to say that improving access isn’t an important goal, just that it is one of many goals and we may not want to reach it by trampling on other goals and creating a world of unintended consequences which end up being harmful to research on balance. If we follow the evidence, we may want to focus first on the highest priority communication needs of researchers instead of on the priorities highlighted by current OA policies. Exactly how these priorities might rank is discussed later in this report.

OVERREACH

Open access policymakers are generally guilty of at least two kinds of overreach. The first kind involves designing policies without possessing the needed expertise. Open access, open science, open data, and other open movements all have different perspectives and priorities. An open science led effort makes no sense for humanities researchers; an open access led effort makes no sense for open data. Today, however, we see a good deal of mission creep, where open access advocates are designing policies having to do with the future of open data, and where plans for the future of journals are designed with STM disciplines in mind, not the humanities. While there is some overlap between these communities with regard to tools and basic principles, they are in fact very different. Therefore, it is ill-advised from a policymaking perspective for open access advocates alone to write such policies—as is the case with Plan S, the UNESCO open science policy, and the US Nelson Memo—since the facts and nuances of all open practice communities are not even remotely captured in policies like these. The reverse situation would never be tolerated by the open access community, where open data advocates working alone decided what the future of open access should look like.

To elaborate on the case of open data, all major open access policies have open data requirements (usually including provisions to make data FAIR—findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable—or to deposit data in specific repositories) but most lack any evidence-based operational details. In truth, open access policymakers (as distinct from the open data experts) have very little grasp of what open data actually looks like, particularly in clinical research where the OA community wants to see faster discovery. This data realm is awash with challenges, such as protecting patient privacy (conforming with existing data protection laws like HIPPA and GDPR), protecting proprietary data (owned by drug companies who sponsor research work), preventing the misuse and misinterpretation of data, and struggling to make the sharing of datasets complete, timely and compatible, even when this data is being generated by the same research group. OA policymakers have not even begun to understand the complexity, diversity, and best practices of this real world sharing, yet they are designing one-size-fits all policies that mandate sharing nonetheless based on open access ideals. Table 2 describes of some of this complexity, and shows how the type of data sharing envisioned by open access policies fits into this array of other data sharing models.

TABLE 2: COMMON DATA GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES AND THEIR ATTRIBUTES

| Governance structure | Number and linkage of parties | Degree of data Availability | Degree of freedom to use data | Challenges common to the governance success | Primary governance design pattern |

| Pairwise | One-to-one | Medium/High | Medium/High | Uneven status of parties, value of data | Informal or closed contract |

| Open Source | One/some-to-many | High | High | Rights permanently granted to user | License |

| Federated Query | Many-to-many, via platform | High | Medium/Low | Defection of creators | Contract and club rules |

| Trusted Research Environment | One/some-to-many | Medium/Low | Medium/Low | Users agree to be known, surveilled | Data transfer and use agreements |

| Model-to-Data | One-to-many | High | Low | Not all who apply can use data | Restricted analyses, data curation |

| Open Citizen Science | Many-to-many | High | High | Capacity for analysis is uneven | Contract or license |

| Clubs, Trusts | Some-to-some | Medium/Low | High | Easy to create things governed more liberally. Trusteeship can be revoked. | Club / Trust rules |

| Closed | Many (to none) | Low | High | Fundamental limits to collaboration | Public laws, security protocols |

| Closed and Restricted | Some (to none) | Low | Low | Fundamental limits to collaboration | Public laws, security protocols |

Source: Mangravite 2020

In the meantime, there is a long list of promising work being done in open data and many success stories to share, but these experiences originate from efforts that have nothing whatsoever to do with global open access policies. For example, there are a number of highly successful research collaboration efforts that demonstrate what the cutting edge of open access development can accomplish (like DataSpace, Vivli, SDSS, CERN, GenBank, DataSphere, and Sage Bionetworks), and what evidence-based data sharing and collaboration challenges exist on the road ahead.

These data sharing networks are most often developed through private partnerships with strict and distinctly BOAI-unfriendly data sharing guidelines and eligibility, not through generalist OA policies and repositories. Open access policymakers have not studied, learned from, or even cited these examples. See Boxes 5-7 on the following pages for more detail.

A second and equally important type of overreach is that policymakers often grant special powers to open that aren’t merited. Take the widely touted claim, for example, that open access increases citation rates. The evidence for this phenomenon is actually not clear, nor is it clear that focusing on increasing citations instead of increasing research quality is the right approach to take (see Box 8).

BOX 5: REAL WORLD OPEN DATA USE POLICIES

OA policies requiring open data deposits are mostly silent on the details that make this data actually useful to researchers, such as data management, vetting, and curation. Leading repositories that already manage vast quantities of research data have designed intricate policies to add this kind of value to open data (which isn’t always openly licensed) as well as to protect discovery, copyright and patient privacy as needed. The data sharing agreements upon which these resources are constructed are legal documents that typically define (at minimum) how long data can be used, for what purpose(s), by what means, what constraints will apply, and financial, confidentiality and security requirements. Many of these agreements (especially in the life sciences) also protect against misuse by allowing only qualified participants to deposit and use data. None of these real world data sharing practices are acceptable under the open data policies designed by open access policymakers, however. Instead, these OA-designed policies only articulate a vision for CC-0 licensed data that is uncurated and available for anyone to use and reuse.

CERN (RAW DATA POLICY)

It is not practically possible to make the full raw data-set from the LHC [Large Hadron Collider] experiments usable in a meaningful way outside the collaborations. This is due to the complexity of the data, metadata and software, the required knowledge of the detector itself and the methods of reconstruction, the extensive computing resources necessary and the access issues for the enormous volume of data stored in archival media. It should be noted that, for these reasons, general direct access to the raw data is not even available to individuals within the collaboration, and that instead the production of reconstructed data (i.e. Level-3 data) is performed centrally. Access to representative subsets of raw data—useful for example for studies in the machine learning domain and beyond—can be released together with Level-3 formats, at the discretion of each experiment. (See CERN 2023)

GenBank

The GenBank database is designed to provide and encourage access within the scientific community to the most up-to-date and comprehensive DNA sequence information. Therefore, NCBI places no restrictions on the use or distribution of the GenBank data. However, some submitters may claim patent, copyright, or other intellectual property rights in all or a portion of the data they have submitted. NCBI is not in a position to assess the validity of such claims, and therefore cannot provide comment or unrestricted permission concerning the use, copying, or distribution of the information contained in GenBank. (See NIH 2023a)

Vivli

(A) Data Use Agreement—All Data Requestors requesting data must execute the Data Use Agreement (DUA). The DUA is the product of extensive negotiation with the organizations that contribute data to Vivli. This agreement is non-negotiable. If granted access to the data, it is for the express purpose outlined in the research proposal. Any changes to that proposal will require re-review and approval by the data contributors involved; (B) Qualified Statistician—All research teams submitting a Vivli data request must include a qualified statistician. The statistician must have a degree in statistics, or similar field, or publications relevant to the proposed research where the individual conducted the statistical analysis; (C) Publication Plan—The dissemination plan must include a definitive statement to publish and disseminate your findings to contribute to furthering scientific knowledge. (See Vivli 2023)

There are, of course, many other examples of how real data sharing is working in today’s research environment (such as DataSphere, CAVD DataSpace, Yoda, and Sage Bionetworks), many high-profile success stories in sharing science data (like CERN, the Hubble Space Telescope, the Human Genome Project and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey), and many other open data research repositories in use (not even including institutional repositories; see https://www.nature.com/sdata/policies/repositories). And owing to the experience and expertise of these groups, as well as to the efforts of the many outstanding organizations working to create best practices in data management and data repository function (such as the Research Data Alliance, COAR, CODATA, JISC, NISO and OpenAIRE), we have also learned a lot about the pros and cons of various data governance structures (see Table 2 on the previous page), and the challenges involved in sharing more research data (see Box 6 on the following page). Our goal with open solutions policies, then, should be to learn from all this history and experience rather than trying to reinvent the wheel. What we may find is that the “imperfect” open approaches that have evolved in the marketplace are the ones that actually work. By learning from these, we can create better and more realistic policies; at the same time, we can help these existing systems operate even more efficiently by bringing them into the fold regarding best practices in open data.

BOX 6: REAL WORLD OPEN DATA CHALLENGES

Competition collaboration, and data sharing are three key drivers in research. Each of these drivers has unique practices, outcomes and challenges, but they are also all closely linked and affect each other. Competition has always been fundamental to the very fabric of research, for example, but as research becomes increasingly complex, collaboration is also increasingly important, and along with this, data sharing as well. Still, relatively few researchers (around 15%) currently share their data outside a limited group of colleagues in any comprehensive and meaningful way (notable exceptions include astronomy, high-energy physics and genomics; see NASEM 2020) due to a variety of concerns and challenges. Similarly, the race to discover has always been a key part of science, but this race sometimes leads to a hyper-focus on secrecy, a temptation to commit fraud, hiding negative findings, and other behaviors that conflict with the needs of good science and open science.

Understanding how these three drivers operate and are evolving in the real world is important for understanding how to improve the research of tomorrow. For example the needs and concerns of researchers with regard to data sharing generally fall into six main categories: Impact, confusion, trust, access, effort and equity.