PDF (VoR)

INTRODUCTION TO THE OSI POLICY PERSPECTIVES SERIES

Back in the Fall of 2014, scholarly communication experts were arguing simultaneously on several different listservs about the future of open access in science. In order to help focus this conversation, our nonprofit—the Science Communication Institute (SCI)—set up a listserv dedicated to discussing this topic in a moderated setting and invited all interested debaters to join in. Dozens of people signed up in the first week, and the list eventually grew to 114 participants, including many of the most recognized names in scholarly communication. Over the next two months this “Open Science Initiative Working Group” developed a comprehensive, multifaceted summary of the scholarly communication landscape (see Open Science Initiative 2015) and also arrived at a fascinating conclusion: We should keep talking. UNESCO pledged it’s support to help bring together even more global leaders in scholarly communication, followed quickly by pledges of support from George Mason University, major publishers, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and many others. A key promise to everyone involved was that we would try to produce results from all this talking, not just reports. We also promised that these results would be based in a common ground understanding of the scholarly communication landscape, arrived at by working together.

Since early 2015 dozens of dedicated volunteers have put in countless hours building the infrastructure of what we later expanded and renamed the Open Scholarship Initiative (OSI). And since early 2016 over 400 scholarly communication leaders have participated substantively in OSI conversations, some more than others. We haven’t ever grown to the point where we can hire enough people to really aggressively follow through on the long wish-list that has been created by OSI participants, but this wish-list itself may be what’s most important. A diverse array of scholarly communication leaders working through OSI has come up with a wide array of recommendations built on common ground. Many of these recommendations have been captured in OSI workgroup reports published on the OSI website (osiglobal.org); many more recommendations have evolved over time through the discussions we’ve had on the OSI listserv.

This report on Plan S and the future of global solutions to open is the first in a series of reports that will attempt to identify the common ground perspectives we’ve discovered over the last few years of working together. They are imperfect documents at best. Some in OSI disagree with publishing these because they might make us seem partisan; others disagree with whether these reports can possibly have the right balance between pro and con sentiments on any particular issue; still others are concerned that we don’t represent the entire global community. All of these concerns are valid, but they need to be evaluated in the context that despite our flaws, we are working together to find common ground. These reports are expressions of this intent. They should be rightly and roundly criticized by all sides for having shortcomings, but these shortcomings are less important than the effort and the lesson that we can indeed work together. It’s a lesson that is timely not just in scholarly communication but society in general. We can choose a future where we demonize those who may have different interests and opinions, or we can actually talk to each other and work with each other to develop real understanding and lasting solutions.

To everyone who has worked with each other in OSI over these past four years, to the funders who have supported this work, and to the universities who have hosted our conferences, thank you.

Sincerely,

Glenn Hampson

Program director, OSI

Executive director, SCI

PLAN S & THE QUEST FOR GLOBAL OPEN ACCESS

In September 2018, a group of EU research funding agencies known as cOAlition S unveiled a plan to rapidly transition the world into a new scholarly publishing system. The central feature of this plan—Plan S—is that starting no later than January 1, 2020, all research funded by these agencies must be published in open access (OA) journals or platforms where articles are free to read and reuse without delay. After this date, these agencies will discontinue funding for publishing in subscription and hybrid journals (which include a combination of open access and subscription articles).

Many of the details about Plan S are at once highly important, poorly understood, hotly debated, and beyond the scope of this summary report to examine in depth. This report touches on only a few of the more salient points of Plan S. In brief, many pathways to compliance with this plan are being promoted and widely discussed. Noncompliant journals can become compliant once they begin transitioning into preferred open formats or business models. Transition terms will be approved for each publisher, price caps or standards will be instituted for the scholarly publishing market (along with a cost waiver system), new global publishing guidelines will be adopted, and as yet unspecified non-compliance penalties will be assessed.

If and when Plan S gets implemented, around 3-5% of scholarly publications worldwide might become subject to its requirements (Pollock and Michael 2018; these estimates have been increasing as new funders sign on). However, the goal is for Plan S to continue to have increasingly important implications for the expenditure of public funds, both in the EU and globally, and to create a more unified global scholarly communication landscape.

Eleven funders were original signatories to this plan. At last count, this number has grown to 15 funders, and the European Commission itself is eventually expected to follow suit. China has also given preliminary indications of support for the principles underlying Plan S (Schiermeier 2018).

SUPPORT VS. CRITIQUE

In the five months between the announcement of Plan S and the publishing of this report, thousands of position statements about the plan have been issued by researchers, commercial publishers, research institutions, funders, scholarly societies, academic groups and other experts. Some of these statements have been supportive of the plan, others have been critical, and still others have been both supportive and critical (see Johnson 2018 for analysis; see the Plan S Wikipedia page for links; see Suber 2018 and COAR 2018 for examples of support letters that also include significant critique). In the words of long-time open access leader Cameron Neylon, Plan S is a Rorschach test where people find whatever they want to find, or don’t want to find.

Sifting through the mountains of position statements and discussions on this plan, what is clear is that no one is arguing against the idea of open access. There are simply lots of different opinions about the best way to reach this goal. This debate has broken along the same fault lines that have separated the scholarly communication community for the past 20 years (as detailed later in this report), but is more strident now because of the proposed scope and timeline of Plan S, and because of this plan’s lack of clarity and detail in places. This has resulted in confusion, misinformation, hurried meetings and improvised explanations, all of which has amplified concerns that this plan is not ready to be turned into global policy. Still, there are those who support Plan S as written and are ready to take a leap of faith that all will end well.

Are we at an impasse? It feels that way to many who have been watching this debate for years. But from a glass-half-full perspective, the scholarly communication community may actually have a lot of common ground to build upon. Consider the statement of Sven Stafström, for instance, director of the Swedish Research Council: “Research will form the basis for solutions to the challenges that we are facing today, but will also lead to entirely new knowledge that is beyond today’s knowledge horizon. It is therefore important that all actors in society have the opportunity to partake of research results…[and that we] enable more people than only those involved in academia to absorb research results in the form of scientific publications.” (SRC 2018)

In his preamble to Plan S the president of Science Europe, Marc Schiltz, speaks in a similar way about the importance of ensuring that research is accessible to researchers. “Universality,” writes Schiltz, “is a fundamental principle of science: only results that can be discussed, challenged, and, where appropriate, tested and reproduced by others qualify as scientific. Science, as an institution of organised criticism, can therefore only function properly if research results are made openly available to the community so that they can be submitted to the test and scrutiny of other researchers. Furthermore, new research builds on established results from previous research. The chain, whereby new scientific discoveries are built on previously established results, can only work optimally if all research results are made openly available to the scientific community.” (Schiltz 2018)

A response to Plan S issued by the Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA) also contains universal aspirations about how Plan S has the potential “to help to coordinate open access policy at an international level, which is in the interests of all stakeholders” (see OASPA 2018). And OASPA’s letter cites Schiltz’s sentiments about the need to “fundamentally revise” the current approach to research evaluation. “Such reform,” writes OASPA, “is essential if scholars are to be empowered to publish in journals that provide them with the best quality of service, value, and wide dissemination, rather than being judged on their ability to publish their work in a limited range of high-prestige journals.” In addition, OASPA applauds the plan’s focus on ensuring that journals and platforms used for open access publishing exercise the highest quality policies and practices and the plan’s commitment to making the necessary funding available so all researchers can publish their work under an open access model.

There is probably even broad global agreement on many of the specific recommendations made by Plan S such as:

- supporting long-term digital preservation programs;

- improving open infrastructure;

- improving global indexing;

- improving the capacity of open journals;

- improving machine-readability;

- making DOI use universal;

- conducting research to improve our understanding of open needs;

- reducing the influence of impact factors; and

- establishing global publishing standards.

There may even be broad agreement on costs, an issue which has catalyzed reform efforts for years—not necessarily agreement on the rationale for these costs but agreement that we need to find a better way to keep costs affordable and/or get more value for our money (such as more open). Publishers might point out that in fact more research is being published today for less than ever before, but cost concerns have figured prominently in this community for years now, lurching from serials crises at libraries to big deal cancellations to Plan S’s intent to completely ban hybrid journals due to their expense (and address the rising cost of transitioning to open in general), to the impasse in subscription negotiations in some European countries (European Commission 2018, Mathews 2017, Else 2018). There is a persistent disconnect between perceptions on the cost issue, and this disconnect as well as the issue itself deserves more attention.

Where real differences of opinion start to emerge in the open access debate is on the issue of value. Critics of the current norms in scholarly publishing question whether the publishing models we’re investing in are the right ones for today’s world, whether our map to the future of scholarly communication is modern and responsive enough, whether we have responded adequately to the challenge of improving access globally, whether change is happening fast enough, and whether our public investments in research should result in free public access to the published documents arising from this research. Cascading from these questions are a torrent of subquestions involving who should make changes, where, what kind, and so on; this is discussed in more detail in the next section of this report.

In all, there are many important, complicated issues to discuss that have not been discussed yet in any inclusive, respectful, comprehensive way at a global level. And absent this, the scholarly communication community has argued instead, with many on all sides who care deeply about the future of scholarly communication in general and open access in particular doing far more talking than listening.

This passion has been divisive, but it has also driven progress. Despite—and because—of lack of communication about our common interests and concerns, we have seen a constant stream of entrepreneurial and even heroic efforts to improve the future of research communication: institutions that embark on their own open solutions, each with their own unique audiences and solving their own subsets of issues, from repositories to peer review to copyright, and attempts like Plan S to make a multitude of changes globally in one fell swoop. Much of this activity is healthy, enlightening and invigorating. Some of it is duplicative, confusing and ill-fated. Very little of this activity is coordinated globally across regions, agencies, institutions and disciplines, however, and even less is developed with broad global input.

Plan S is not the first attempt at global change nor did it emerge out of thin air. In fact, many of its principles (see the sidebar on page 2) grew out of a variety of previous EU policy documents, policies and mandates (Kingsley 2018). Plan S also complements the principles embraced by the Open Access 2020 Initiative (OA2020), which includes over 120 individual and umbrella research organizations on five continents and is coordinated by the Max Planck Digital Library on behalf of the research community. The objective of OA2020 is to accelerate the global transition to open access by repurposing subscription funds to support publishing models that produce open and reusable content, and for which costs are transparent and economically sustainable. OA2020 continues to gain momentum globally (see the OA2020 website for details) but more participation from the global research community is required.

In summary, the motivations behind Plan S are deep, sincere and widely held, underpinned by years of dreaming about and trying to achieve more open, and constantly spurred on by concerns about the rising cost of access, and about seemingly slow progress on open, reform plans that address only a few problems at a time, overall approaches that seem ill-suited to meet our future challenges, and a stakeholder community that has been arguing for decades. It’s understandable why many support an attempt to reform scholarly communication with a bold, sweeping, global effort, even if this effort is less than ideally constructed. The impulse to back Plan S is undeniable and may in the end be correct. But apart from these sentiments, is Plan S actually the right solution—not the right sentiment but the right policy instrument? This is the question we try to answer in this report.

OSI’S OBSERVATIONS

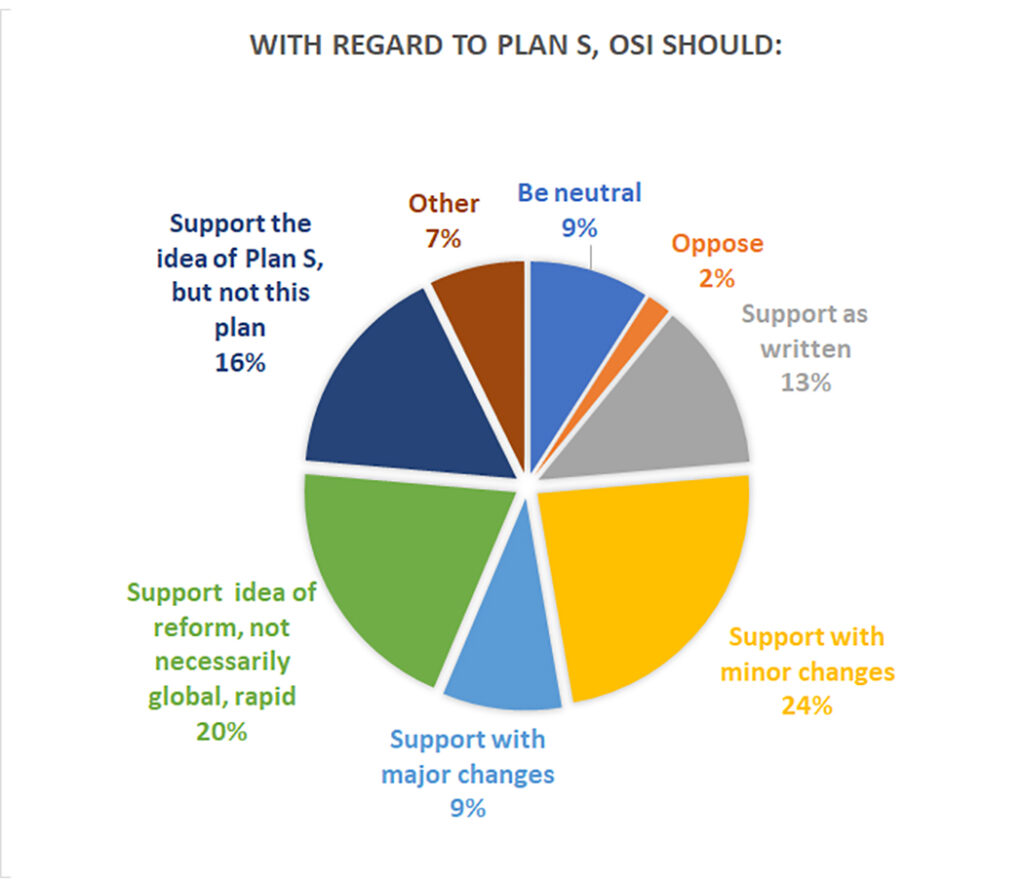

OSI is a varied group with a wide variety of opinions. In a recent survey of the OSI listserv (see above notes for figures 1A and 1B), about a third of OSI feels the future of scholarship should be one in which all research is made freely and immediately available without any restrictions on access or reuse. Two-thirds think this future should look like something else— the most popular position (about 45%) being that more but not necessarily all scholarship should be immediately and freely available. With regard to Plan S itself, most OSI respondents did not support this plan as written; about 37% were willing to support it as-is or with minor changes.

Underlying these responses and the entire wide-ranging multi-stakeholder conversations that have been happening in OSI since 2014 are many different perspectives on the fundamental who, what, why, where, when and how questions of scholarly communication reform:

- Who has the right to reform the scholarly communication system for everyone and on what authority? Who decides this question?

- What interests should be considered and how should they be prioritized? Different people see different problems—escalating library costs, undiscoverable work, poor transparency. Which goals should we tackle first? And at what scope? Should we aim for completely open research processes or just OA?

- Why? What problem(s) are we trying to solve? Is the system broken or just in need of adjustment?

- Where? Should reform happen EU-wide? Globally? Institution-by-institution, and then develop lessons of experience and best practices to roll out?

- When? Should major changes happen immediately? Gradually? At some point in the not too distant future? How urgent are the issues we’re trying to solve?

- How do we get behind good ideas and make them work? Collaboration? Cooperation? Mandates? New incentive structures? Fundamental reform of incentive and reward structures?

As a group representing a wide variety of opinions across the scholarly communication landscape our survey results provide only a tiny window into how the global stakeholder community might feel about Plan S (including libraries, funders, policy officials, university leaders, publishers, scholarly societies, researchers, non-university research institutions and other groups). While we can’t draft statements that speak for everyone in our group it may be fair to say that a majority in OSI sympathize with the sentiments of Plan S (as expressed by Stafström and Schiltz) and may even agree with many of the plan’s specific goals. Our common ground is probably significant.

Our main differences about Plan S seem to center around—as mentioned earlier—a lack of clarity with regard to exactly what this plan is proposing, and also differences of opinion about how to achieve our common goals of improving open while at the same time balancing other important interests—the who, what, why, where, when and how questions. With regard to these differences, the main critiques about Plan S that have been discussed in OSI include:

1 This debate is all very sudden. Plan S seemingly came out of nowhere—not the debate underlying Plan S, described earlier as decades in the making, but the plan itself, which did not grow from a public, transparent process. Still, surprise notwithstanding, is it a well-thought out proposal developed with broad input and a deep understanding of the scholarly communication ecosystem? To critics the answer is no. Even many supporters agree there is room for improvement. It’s important to understand that all these people aren’t opposed to Plan S per se. Many are simply concerned that the details and potential consequences of this plan have not been carefully and broadly considered yet and that important stakeholders in the current system (notably working researchers) were apparently given little opportunity to provide input into the formulation of its principles.

We know the general history behind Plan S—developed by Robert Jan-Smits, the European Commission’s special envoy on open access, together with the heads of the participating research funding organizations and the president of Science Europe. But what input did this group consider (beyond a small survey that was undertaken) and over what time frame? What options were evaluated? Who provided input and what were their conflicts of interest? What decision process was used to arrive at the plan’s recommendations? And perhaps most important of all, how will public feedback on the plan be weighed and incorporated?

2 What do we mean by open anyway? This question continues to underpin much of the misunderstanding and confusion that currently exists in scholarly communication discussions about open reform (OSI Issue Briefs 1 and 2; Moore 2017). The definitions of open access most frequently cited by OA advocates come from a series of small meetings of advocates held in Budapest, Bethesda and Berlin (3-B) in 2002, 2003 and 2004 respectively. Proponents of the definitions developed at these meetings believe there is only one “legitimate” kind of open: articles that are both free to read and also free to reuse without restriction (free-to-reuse articles typically carry a Creative Commons CC-BY license). In practice however, many different kinds of open have evolved in the scholarly communication marketplace over the last 20 years, as have a variety of open practices between fields (open source, open code, open educational materials, and more). Indeed, even within 3-B compliant open a variety of interpretations have emerged.

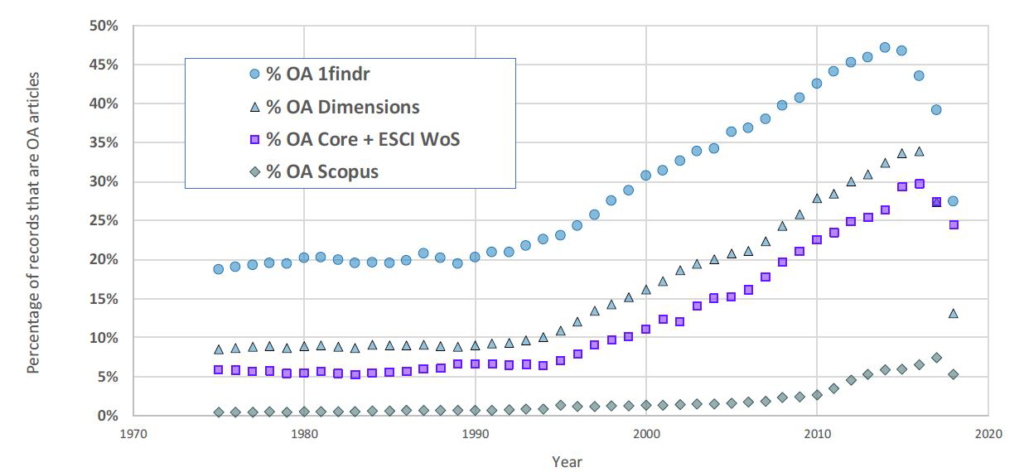

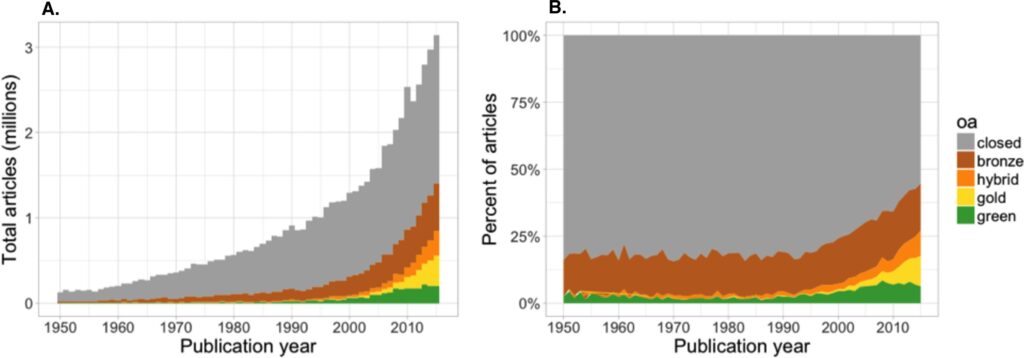

OSI therefore considers open to be a spectrum of outcomes, varying with regard to discoverability, access, reusability, transparency, and sustainability (DARTS; see OSI brief 1). Looking at this broad open spectrum, a recent study by Eric Archambault (see figure 2A) shows that we’ve actually made a significant amount of progress on open over the last 20 years if one considers “free to read” as being open and not just 3-B compliant forms of open. If, however, one considers only 3-B compliant open as legitimate, then indeed open has grown much more slowly. A recent study by Piwowar et al. 2018 (see figure 2B and table 1) illustrates how different kinds of open have grown over time. Of these types, only gold and hybrid are wholly 3-B compliant.

TABLE 1: PIWOWAR 2018 ESTIMATES OF AMOUNT OF OPEN ACROSS THREE SOURCES

| Type Of Open | Crossref DOIs: All Journal Articles With Crossref DOIs, All Years | WoS DOIs: All Citable WoS Articles With DOIs, 2009–2015 | Unpaywall DOIs: All Articles Accessed By Unpaywall Users Over A 1-week Period In 2017 |

| Open (all types) | 27.9% | 36.1% | 47.0% |

| Bronze | 16.2% | 12.9% | 15.3% |

| Hybrid | 3.6% | 4.3% | 8.3% |

| Gold | 3.2% | 7.4% | 14.3% |

| Green | 4.8% | 11.5% | 9.1% |

| Closed | 72.0% | 63.9% | 53.0% |

Source: Adapted from Piwowar et al. 2018

Ensuring that articles are immediately free to read is also important to many OA advocates. The Budapest and Berlin declarations don’t speak directly to this issue; Bethesda only mentions the need to have “immediate” deposits made. This immediacy issue arises primarily because articles in subscription journals can be withheld from public view either temporarily or permanently. If temporary, this delay—known as an embargo period—typically lasts for around 12 months. At present, around 50% of recently published articles (Archambault 2018) and 70% of all articles historically (Piwowar et al. 2018) are permanently hidden from view, although how much of this is due to embargo is unclear—many articles are simply undiscoverable because they aren’t online. For embargoed materials, Archambault notes that as embargo periods expire, our historical estimates of how much open exists are being revised upward at a rate of about 4% per year.

While inconvenient for some researchers, and arguably damaging for research in fast-moving fields (although research is needed on this point), embargoes are also important for many researchers in the humanities and social sciences where monographs destined to become retail books are the norm instead of journal articles. Typical embargo periods in history can last years instead of months, allowing more time for books to be edited, published and marketed. Simply eliminating embargoes, therefore, isn’t necessarily a workable solution for all scholarly publications everywhere. The same argument applies to simply mandating CC-BY: humanities works aren’t just a collection of facts that authors want to release to the public for free reuse. In short, the 3-B’s are seen by many as STM-centric definitions of open access—the “unique” concerns of humanities and social science researchers are given little to no consideration (see AHA 2019 for the American Historical Association’s perspective on Plan S).

The US Public Access program—which accounts for the world’s largest archives of free-to-read research articles (including PubMed Central)—sought a middle ground on this disagreement years ago by building in flexibility with regard to copyright and embargoes, focusing instead on ensuring free-to-read access (hence the program’s “public access” moniker rather than “open access”). By so doing it staked out a position on the part of US government funders that essentially says “free to read after embargo is sufficiently open.” This is a significant position insofar as the US government is the single largest funder of research conducted at US higher education institutions, and the US has the world’s largest research and development budget and produces the most research papers (with the possible exception of China in recent years; see NSB 2018).

In OSI we haven’t taken sides on which approach is better—CC-BY with no embargo, copyright with embargo, or some combination of these—but we do frequently come back to the observations that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to open, and that open has been developing along a spectrum of outcomes for many years now, including green, gold, bronze, platinum and other variants. Different outcomes are growing faster for some fields than others and the argument for immediate reusability is stronger and more immediately achievable in some fields than others (especially in fields like computer science where open source code is extremely valuable, or medicine, where accelerating discovery may save lives). Effectively advancing open, therefore, can arguably involve a broad and flexible approach—albeit imperfect in the moment—and this approach can and should evolve over time.

3Is more green a worthy goal unto itself? (Yes.) Green open access is where research articles get self-archived into free-to-read digital repositories and platforms. These information buckets can range from small institutional repositories (IRs) at universities, to large subject repositories, to giant multi-discipline repositories like arXiv and PubMed Central, to journal-run platforms. In addition to containing articles, green buckets often also include datasets, white papers, presentations, dissertations, conference proceedings and more.

The publishing-related characteristics of green journal articles varies widely, from pre-prints to official versions of record, from publisher-copyrighted material to CC-BY licensed, from immediately available to embargoed. For most articles in most fields—with some notable exceptions—green usually happens in addition to or in conjunction with publishing in journals (referred to hereafter as “shadowing”), not instead of. See Björk et al. 2014 for a more complete discussion of this form of open (the figures are a bit dated now but the analysis is still useful).

There is also overlap between green and “bronze” open (see figure 2B and table 1), which is a larger and faster growing type of green (indeed, bronze is the largest and fastest growing of all types of open). Piwowar defines bronze as green articles that are hosted on a publisher’s website, so green and bronze can be similar except for the location of hosting. (One concern about bronze is that being hosted on a publisher’s site may be a less permanent open solution than being hosted in a public repository like PubMed Central; see Poynder 2017 for discussion.)

Of all the spaces in scholarly publishing today, green (including bronze) is the most varied and dynamic. For many open advocates, green is also seen as the easiest and most realistic path to achieving more open a lot faster than by waiting for the culture of communication in academia to slowly change. So why doesn’t Plan S come out strongly in favor of green and focus first and foremost on finding ways to help this kind of open grow? Maybe because “rebalancing” Plan S toward green might imply a watering down of the plan’s goals. In particular it might mean backing away from the plan’s stated goal of eliminating subscription publishing and would also suggest a lack of appetite for tackling the flawed reward structures that contribute to many of the problems in the current scholarly communication system. It is important to acknowledge these tensions when evaluating criticisms of Plan S’s approach to green.

With regard to these criticisms there are primarily three to consider:

- Definitions: Because some of the language in Plan S is so imprecise it can lead to misperceptions. In this case, one might be led to believe—whether or not this is the intent—that Plan S only considers articles to be green if they are non-embargoed, official versions of record or author accepted manuscripts, licensed in CC-BY format and hosted in a public repository for broad public sharing and consumption. This definition isn’t used in scholarly communication and doesn’t align with the actual, diverse nature of green. Maybe green shouldn’t be diverse but as with open itself, green exists and is defined along a broad spectrum of outcomes, with the common denominator being free-to-read. Plan S’s definition or lack thereof doesn’t acknowledge green as we understand it, which leaves a lot of value on the table in our quest for more open. It can be argued of course that pushing for more openness in green is a good thing, but it can also be argued that requiring this improvement in one giant leap may result in less green, not more. That is, if authors are told that green means CC-BY or nothing then nothing may be the right choice for many.

- Emphasis: Plan S doesn’t treat green as an end point in our quest for open but instead as a subset of other preferred outcomes (see MIT Libraries 2019). The plan’s implementation details specify three main routes to these outcomes: (1) Publish now in a Plan S-compliant journal or platform; (2) Immediately upon publication, deposit the final published version in a Plan S compliant repository under a CC-BY license and without embargo; or (3) Publish CC-BY in a subscription journal that is covered by a transformative agreement. Under routes 1 and 3 the emphasis is on achieving open through open journals or platforms such as F1000 or Science Open. Under route 2, green is mentioned but only as something that happens “upon publication.” This “upon publication” condition is problematic because subscription journals typically do not allow the kind of green that Plan S requires. Therefore, in the current publishing landscape the most likely way for authors to comply with Plan S through route 2 is to first publish in a gold or other compliant journals or platforms or in subscription journals that don’t perceive a threat to their revenues from Plan S-compliant green.Obviously the carrot here is to encourage more publishers to change their practices to allow more green, but using journal reform to accomplish this is a more convoluted approach than simply focusing directly on green to begin with. That is, if subscription publishers were indeed willing to discuss ways to improve pathways to green—bearing in mind that most green is simply free-to-read and not also CC-BY licensed and immediate—then the amount of green open could grow quickly and dramatically. But the assumption in Plan S is that subscription journal publishers will not agree to this approach and therefore abolishing subscription journals is a necessary first step.

- Foresight: Plan S is silent on what a future with a lot more green might look like and what kind of downstream issues the scholarly communication community should anticipate. A large, coordinated, substantive shift to green will require different kinds of incentives, more flexibility and a lot more thinking and planning. Some of the issues that will need to be planned for in this future include:

- Disruption: What might happen if a lot more researchers start posting final versions of their work to Plan S compliant repositories? First of course, these repositories need to be created (not necessarily from scratch) since most of those currently in existence don’t comply with requirements set forth in Plan S. The Coalition of Open Access Repositories—COAR—has issued a detailed statement in this regard (see COAR 2018). But if this happens and if researchers start using these new repositories en masse then scholarly communication norms could change significantly—including less demand for journals and less capacity in more fragile journal systems—small society publishers and university presses, for instance; widespread changes to what can be posted on existing repositories, particularly with regard to requiring versions of record and eliminating embargo periods; and possibly a need to replace the filtering and signaling functions that journals currently provide. These aren’t “good” or “bad” outcomes, just different from the way things work today. Are we prepared for this kind of shift or are we simply hoping the “good” will outweigh the “bad?” And can all these changes happen anyway unless incentives also change? Researchers won’t skip publishing anytime soon in favor of just posting more pre-prints after all, unless the publish or perish culture in academia also changes.

- Demand: Green OA varies widely by region (see table 2). Eger and Scheufen 2018 also note there is wide variation by discipline, with publishing practices falling into three distinct publishing cultures: (1) The gold open culture (generally the life sciences) with high use of OA journals but little use of repositories (gold open is discussed in the next section); (2) The green culture (generally physics, astronomy, math and business) with little use of OA journals but strong use of repositories; and (3) The gray culture (including social sciences, engineering, and chemistry) with mediocre use of both gold and green open access. There will be different levels of demand for a greener world. Ideally then, Plan S should be flexible and facilitate the growth of green in regions and disciplines that are open to this rather than pushing solutions that won’t work for everyone everywhere. That is, if more open is our common goal as opposed to one-size-fits-all solutions for achieving more open, and if pushback from certain groups, regions and disciplines is going to sink the entire plan, then why not be flexible in our thinking so we benefit now where we can, particularly with regard to a type of open that is already as robust and diverse as green?

- Interoperability and sustainability: As research repositories proliferate so too do interoperability and sustainability issues. Institutional repositories in particular have a spotty record—they are expensive to maintain and are not widely used (although some institutions are very good at operating IRs and have a long record of success). Plan S also mandates new requirements for repositories, but this is an untested and unproven expansion. Ideally, we should develop requirements in concert with repository managers as noted in the COAR response, and consider phasing in these requirements over time in order to test the compliance and resilience of this network before relying on it. We should also not ignore the prospect of building fewer and larger mega-repositories (see the All Scholarship Repository discussion in OSIWG 2015), both to limit our interoperability and sustainability risks and also enhance the prospects of creating more value from truly vast databases of research knowledge.

What does all this mean? It’s hard to say. These questions and more don’t suggest a lack of enthusiasm for green—just the opposite. More green may indeed be the path that gets us to an open world faster and easier than any other option, but Plan S isn’t focusing on enabling and expanding the existing rich and diverse ecosystem of green. Rather it is focusing on creating a strict new shadow outcome for green—free-to-read, immediate, free-to-reuse, official versions of articles in approved repository environments. These choke-points may be well-intentioned but they don’t align with the reality of green at present, which isn’t to say that this reality is ideal, just that we should at least endeavor to speak the same language on this issue. And of course if we’re going to really advocate for vastly increasing the scale of green then we should also look carefully at what kinds of ripples this shift might cause so we can ensure at minimum that research integrity is protected. More study is needed here.

In all, Plan S as currently written is unlikely to increase the growth rate of green open. Most researchers in most fields will continue seeking out opportunities to publish their work in journals and when it comes to publishing their work—assuming researchers accept the new publishing options created by Plan S (discussed in the next section)— then under this plan green will just continue to marginally increase over time as a shadow output. If researchers rebel and choose noncompliant publishing options instead, green will also still grow (albeit noncompliant green). Where Plan S does potentially affect the future of green is by trying to alter the definition of green and also by introducing more structure and standards for green repositories. Both of these changes need to be community-led, not decisions made by any one stakeholder group or agency.

TABLE 2: OPEN ACCESS LEVELS BY OA TYPE FOR THE TOP PUBLISHING COUNTRIES (2014)

| REGION | PAPERS | OA TOTAL | GREEN | GOLD | UNDETERMINED |

| World | 1,490,237 | 55% | 31% | 23% | 12% |

| United States | 397,773 | 63% | 38% | 24% | 14% |

| China | 281,277 | 46% | 23% | 22% | 8% |

| United Kingdom | 111,666 | 67% | 36% | 28% | 28% |

| Germany | 104,695 | 57% | 36% | 25% | 14% |

| Japan | 78,193 | 50% | 24% | 27% | 11% |

| France | 72,648 | 64% | 46% | 22% | 14% |

| Canada | 65,918 | 60% | 36% | 25% | 14% |

| Italy | 65,505 | 62% | 42% | 23% | 13% |

| India | 58,439 | 49% | 34% | 16% | 8% |

| Australia | 58,118 | 61% | 38% | 23% | 18% |

| Spain | 57,530 | 62% | 38% | 22% | 18% |

| Rep. of Korea | 54,977 | 49% | 25% | 25% | 10% |

| Brazil | 41,315 | 74% | 42% | 41% | 11% |

| Netherlands | 38,902 | 68% | 42% | 28% | 21% |

| Russia | 30,915 | 45% | 35% | 10% | 9% |

| Switzerland | 28,764 | 67% | 41% | 28% | 23% |

| Iran | 27,815 | 51% | 32% | 19% | 9% |

| Turkey | 27,324 | 54% | 30% | 22% | 14% |

| Sweden | 25,896 | 66% | 43% | 29% | 19% |

| Poland | 25,314 | 62% | 34% | 29% | 14% |

Note: These categories are not mutually exclusive—e.g., a gold paper can also have a self-archived version (green OA).

Source: Science-Metrix 2018. Prepared by Science-Metrix using the Web of Science and the 1Science database.

4 Should we really go for the gold? Gold open is a varied landscape. It is generally growing more slowly than other types of open and accounts for about 7% of the total number of journal articles published (Piwowar et al. 2018) and 23% of the total number of open articles (Archambault 2018; estimates vary depending on the time periods considered, databases used, how open is defined, and more). As is the case with other publishing formats, the use of gold open varies widely by field and by country; country variation is noted in table 2.

It costs money to publish in any manner—even in gold open access journals. Rather than getting this money from readers via subscriptions, around 70% of gold journals are supported by institutional subsidies, advertising, grant funding, society membership dues and/or volunteer efforts. The remaining 30% are supported by APCs, or “article processing charges.” In APC-funded journals, fees paid by funders, authors, institutions, libraries and other sources cover the cost of publishing accepted articles. The large asterisk to this characterization is that most gold articles themselves are paid for by APCs (Pinfield 2017, Crawford 2015; Bjork 2018 notes this figure may be around 70%—with 129,000 “free” open articles versus 293,000 paid by APCs in 2016). The availability of APC funds varies widely by institution; across all open journals, APCs are paid by authors about half the time (Parsons 2016).

The scholarly communication community’s vocal disagreements about the merits of gold open, then, centers around these two different visions of the future—gold as a vibrant and widespread platform where more institutions foot more of the bill for open; or gold as a small and slow-growing platform supported disproportionately by author-paid APCs. Each vision is underpinned by different sets of facts, which often results in knowledgeable advocates finding little common ground on this issue.

Scale may be the real culprit here. What’s interesting about this disagreement is that the disparity in facts tends to disappear on a more local scale: Going for more gold makes perfect sense for some countries and fields. Brazil, for instance, leads the world in gold OA publishing due to the brilliant and pioneering work of SciELO over several decades, and Brazil will continue to expand on its success with gold. It’s understandable that other countries might want to try to emulate Brazil, although this will take time since SciELO is so highly influential and developed and Brazil has well-established APC funding channels. The EU has experimented with gold for the past several years and has seen overall gold adoption increase, though not yet to Brazil’s levels (in the UK, gold has increased from about 17% to about 20%; see Jubb et al. 2018).

So, given all this background, what are some of the concerns about the global gold model of open? One is cost. Cost savings are promoted as a potential benefit of Plan S so it’s important to understand whether this is true so we can judge this plan on its merits. The reality is that we just don’t know for sure. A recent Wellcome Trust analysis found that average APCs have been rising 7-11% annually—about double to triple the inflation rate (Wellcome 2018a; whether these trends will continue is debatable, of course). Given this, will gold end up being more expensive than subscriptions over time? This issue needs more monitoring and study (Jubb et al. 2018). Even the cost savings of gold over hybrid is questionable. A recent Delta Think study showed that gold APCs are set to overtake hybrid APCs by around 2020 (Pollock and Michael, 2018a).

What is clear is that researchers don’t comparison shop for the best APC prices (Mudditt 2018, Tenopir et al. 2017, Feng 2013). Rather, their incentive is to publish in high status journals, which carry higher price tags. Why does this matter? Because like the subscription model Plan S seeks to replace, the gold model is not as diverse as we might imagine. Currently, most gold articles get published by just a handful of major publishers and in a few major megajournals (such as Scientific Reports and PLOS ONE; see Piwowar et al. 2018; this dovetails with the findings in Larivière 2015 that most journal articles are published by just a handful of publishers). The APCs for this concentrated group are priced higher than the for the majority of gold open journals—the mean APC for all gold open articles is in the US$2,200 range and around US$1,300 for megajournals (APC prices fluctuate widely from a few dollars to five thousand dollars and up; see Siler et al. 2018). In contrast, the median APC for the 29% of gold open journals listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) and charging APCs is around $600 (Morrison 2018).

So here again, we have competing visions of the world supported by competing facts. One vision asserts that more authors will be able to publish in $600 (or free) DOAJ-listed journals and save the system lots of money. Another competing, equally valid vision is that more authors will continue to seek out and publish in the most popular journals, which are higher priced and highly concentrated, which will end up costing the system more money.

Another concern provoked by the idea of a rapidly rolled-out gold world—assuming author choices continue to skew toward large publishers and megajournals—is that flipping from paywalls to “play-walls” may result in researchers from less wealthy institutions everywhere, including but not limited to the global south, becoming less able to publish than now (Green 2019). Evidence today is that even very modest APCs in the range of a few hundred dollars may be unaffordable for many authors in the global south (Scaria and Shreyashi 2018; INASP 2018; Minai 2018). This unaffordability may end up amplifying the already existing north-south gap in research caused by high subscription prices, as well as the Matthew Effect in science wherein higher-status scientists are able to parlay their existing status into further cumulative advantages. Siler et al. 2018 backs up this latter point:

Findings show that authors working at lower-ranked universities are more likely to publish in closed/paywalled outlets, and less likely to choose outlets that involve some sort of Article Processing Charge (APCs; gold or hybrid OA). [With regard to institutional differences and stratification in the APC costs paid in various journals], authors affiliated with higher-ranked institutions, as well as hospitals and non-profit organizations pay relatively higher APCs for gold and hybrid OA publications. Results suggest that authors affiliated with high-ranked universities and well-funded institutions tend to have more resources to choose pay options with publishing. Our research suggests new professional hierarchies developing in contemporary publishing, where various OA publishing options are becoming increasingly prominent.

APC waivers have been proposed as a way to mitigate these affordability concerns, but there is currently a lack of detail in Plan S about how many waivers would be needed, who would pay and how much cost-shifting would have to occur, so the enthusiasm for this approach is understandably muted at the moment. Waivers may end up working well—we just don’t know yet.

Still another concern along these same lines is that an all-gold world may result in global south researchers essentially subsidizing Western science since these APCs represent a much higher percentage of their research and publishing budgets than for their northern/western counterparts (Ellers 2017).

Finally, to contain APC costs, price controls have been proposed (caps or standards—specific guidance has been shifting; see the 2019 Academic Publishing in Europe conference website and Twitter feed for details). Price caps have already been used to a limited degree in publishing but never before at this scale or range. The risk of this approach is that as in any market situation, these kinds of controls can cause distortions—in this case, for instance, overcompensating bad publishers and undercompensating good ones—and/or lead to unintended consequences such as lower quality or cost-shifting, resulting in even higher prices for EU researchers, not lower. Also important is the impact that APC controls might have on the function of rigor that many appreciate from the top journals in their fields. If APCs are capped in such a way that the financial viability of a given title is threatened, then this journal may have no alternative but to accept more manuscripts of lower perceived quality. Given the popularity of megajournals, some believe this filtering function of journals is no longer needed or relevant anyway, but based on our conversations in OSI as well as the continued desire of just about everyone in academia to publish in top journals if and when they can, filtering is still critical and is more time-consuming and expensive for some journals than others. There is also the issue of invited content—reviews and the like that are vital for fields to be synthesized and progress. Who will want to pay an APC to publish a review? Even current OA journals don’t seem to charge for these. How will such articles be handled? (Barrett 2019)

There is understandably a certain amount of skepticism regarding predictions of doom and gloom for a price-controlled global gold model because not all price control schemes are created equal. But there is equally as much skepticism about predictions that price controls will work because no model supporting this aspect of Plan S has been constructed yet.

So, overall then, is the idea of global gold good or bad? The jury is still out on this question—there are still lots of unknowns about whether and how this idea will work. At one point, OA2020’s calculations showed there is enough money in the system to make a global flip to gold publishing possible, factoring in all the necessary discounts and subsidies that would be required. These calculations have not been disputed but they do need to be updated and confirmed, as well as calculations regarding price controls, market impacts and more, before the global scholarly communication ecosystem can fully embrace any plan that has global aspirations.

And then there’s the question of “if” this idea should even be attempted at all. A global shift to gold may well be the greatest idea ever, but so too may a shift to green or a shift to other kinds of open emerging in the market (see Suber 2018). If any global plan is going to pick winners then it needs to consider more evidence than has been considered so far.

5 What about academic freedom? Many researchers think Plan S infringes on academic freedom by restricting the ability of authors to choose for themselves how and where to publish. It has been suggested that this interference might cause harm to researcher careers in terms of the promotion and tenure credit they receive, might disadvantage EU researchers subject to these restrictions and might even harm research itself by interfering with the international communication process that is so critical to scholarship.Closely related to these concerns is the question of author rights. Many believe that letting authors maintain some level of control over the work they create is to a very real degree a moral issue, just as many also believe that opening up research is a moral issue. And this means the debate about Plan S—as if it wasn’t complicated enough already—takes on an added, philosophical dimension in which we’re arguing about how to balance the rights of individuals with their obligations to serve the best interests of the community. These situations always pose at least two classes of problem: (1) Do we agree what “the best interests of the community” are?; and (2) Assuming we do, then do we agree about the degree to which individuals ought to be free to make decisions that don’t serve the best interests of the community? We deal with these problems in society all the time. Speed limits, compulsory education and tax laws all reflect decisions we’ve made as a society about where the right balance is between freedom and coercion, and between the rights of individuals and the needs of society. Plan S is generating controversy not only because there are mixed opinions about whether this plan serves the best interests of the community, but also because there are mixed opinions about how to best balance the rights of individuals with community obligations

6 What happens to publishers? Perhaps ironically, the highest profile “targets” of Plan S—large commercial publishers—will be easily able to weather the impact of this plan due to their size and diversity (Taylor & Francis Editors 2018 plus private communications). The biggest impact may end up being on the diversity of the publishing ecosystem—particularly small, single revenue source publishers (both for-profit and not-for-profit) and scholarly societies (AAP 2018).In the case of scholarly societies, these rely on a variety of publishing models to serve their members, including subscription and hybrid (Clarke 2018). Because Plan S focuses on eliminating funding for subscription and hybrid journals and instead favors a gold pathway to compliance, scholarly societies may find their financial situations imperiled (noting here, of course, that many societies already finance fully-OA journals through their membership fees; see McNutt 2019 for a fuller discussion of the potential impacts of Plan S on scholarly societies). One of the unintended consequences of Plan S, then, may be to force some of scholarly societies to partner with major commercial publishers, which could create more industry consolidation and even higher industry profits. Wellcome/UKRI has commissioned research into helping scholarly societies figure out how to adapt to Plan S (Wellcome Trust 2018).

7 Will this lead to more regulation of scholarly publishing? The range of market controls proposed under Plan S is significant, from APC price controls to the defunding of subscription and hybrid publications to the establishment of publishing rules and regulations, and more. It is worrisome to some how far this regulation will go and whether allowing this degree of influence is warranted given the risks involved in destabilizing the scholarly publishing industry and its ability to carry out the critical functions it provides to research. Here again, skepticism about this point of view is allowed because many industries are regulated. As a rule, though—at least in democratic institutions—this kind of regulation is done with careful thought, great care, and also transparency. This does not seem to be what is happening with Plan S, at least yet.

8 Plan S implementation details include a variety of minor “issues.” Some of the more problematic ones are listed below. It’s possible that these can be corrected as part of the feedback process:

- Currently, the compliance standards relied upon by this plan have been developed by non-governmental agencies who have no official authority or accountability to government regulators or the stakeholder community.

- The technical compliance standards that have been proposed may be beyond the reach of many small publishers.

- There is a lack of clarity with regard to who gets to decide what transformative agreements look like and also concern about whether smaller publishers with fewer resources will be at a disadvantage in the transformation agreement negotiation process (Cochran 2018).

- Some of the current provisions in Plan S may be contradictory, contain loopholes or be potentially unworkable as written. More editing is needed. For instance, the language surrounding hybrid non-compliance is unclear. If authors publish on an OA basis in a hybrid journal (with a CC-BY license), there’s nothing to prevent them from putting their articles immediately and without embargo into Plan-S-compliant repositories. So does this workaround make hybrid journals compliant and therefore permit authors to use cOAlition-S-provided grant funds to cover their APCs (and if not why not)? In terms of potentially unworkable rules one such example is the plan’s requirement for publishers to make their books transparent, which may ultimately violate antitrust laws.

- Considering the sum total of compliance standards currently required under Plan S, it’s possible that upwards of 91 percent of open access journals are not compliant (Frantsvag 2019). The challenge of ensuring that so many journals become compliant in so short a time period has not been addressed—for instance, total costs to governments, funders, institutions and so on (not to mention the administrative costs for Plan S).

9More. Table 3 at the end of this brief compiles these observations and a few more as they relate to the ten principles of Plan S and the plan’s implementation details.

OSI’S RECOMMENDATIONS

OSI’s purpose is to bring the scholarly communication community together to better understand each other’s perspectives and find common ground on globally workable and sustainable solutions. Not everyone thinks this common ground exists, or that if it does exist we can ever find common ground solutions acceptable to everyone.

We acknowledge these criticisms and the difficulty of this challenge but at the same time recognize that after four years of debating the future of scholarly communication we’ve already uncovered a lot of common ground which deserves to be explored. The OSI summary reports for 2016, 2017 and 2018 provide more details (OSI workgroup proposals from these meetings will be summarized in a future OSI Policy Perspective report). In a very general, high-level sense we all agree, for instance—despite our many differences on details—that the current scholarly communication system can improve, that open is worth working for, and that there are many pathways for change, many issues to consider, and many ways of looking at these issues. Perhaps most importantly, we all agree that we should work together on the challenges ahead. This perspective is captured by these four pillars, developed by OSI’s 2018 summit group as the foundation upon which the future of open should be built:

1 Research and society will benefit from carefully planned open. Open represents a fundamental shift for research and researchers. Changes to the current system need to made thoughtfully and diligently and we need to measure the impacts of these changes along the way. How patient do we need to be? Granted there can be a fine line between working deliberately and exhausting everyone’s goodwill with slow and incremental progress, but it’s also important not to set ourselves up for failure by believing that the entire scholarly communication puzzle can be solved overnight. Some parts of this puzzle can and should be tackled immediately (the edge pieces if you will); other parts will take time.

2 Open exists along a spectrum of outcomes. All kinds of open are growing. If we embrace this full spectrum of outcomes we can start focusing on what really matters—getting more of the world’s research information open quickly and working together on building the framework for actually using this open information to benefit research. Getting there is just step one. Figuring out what to do with open (and guiding this process) is equally important if not more so.

3 Connected issues need to be addressed simultaneously, from peer review to impact factors to embargoes, deceptive publishing, publishing standards, indexing and so much more. Unaddressed, these systemic issues will corrupt whatever plans we design and will keep the full potential of open in check.

4 Successful solutions will require broad collaboration. The global stakeholder community needs to be connected and involved in developing and rolling out open solutions. There are so many organizations doing good and important work in this space. By leveraging our assets and coordinating our work—at least at the margins—we can work together on capacity building, innovation, best practices, education and outreach, pilot programs, financing, and so much more, and together we can all pull for open in the same general direction. This collective effort is much needed and the benefits of this effort will be enormous and give confidence, stability and vitality to the open scholarship space while also achieving maximally beneficial solutions by drawing on multiple perspectives and respecting the rights of all parties in the system. The drivers of this process can be funders, governments, open advocates, publishers, researchers, universities, libraries, or all of the above like now, but the customers—the researchers—also need to judge what works and doesn’t work for research and these customers need to play an integral role in designing and refining our open solutions over time.

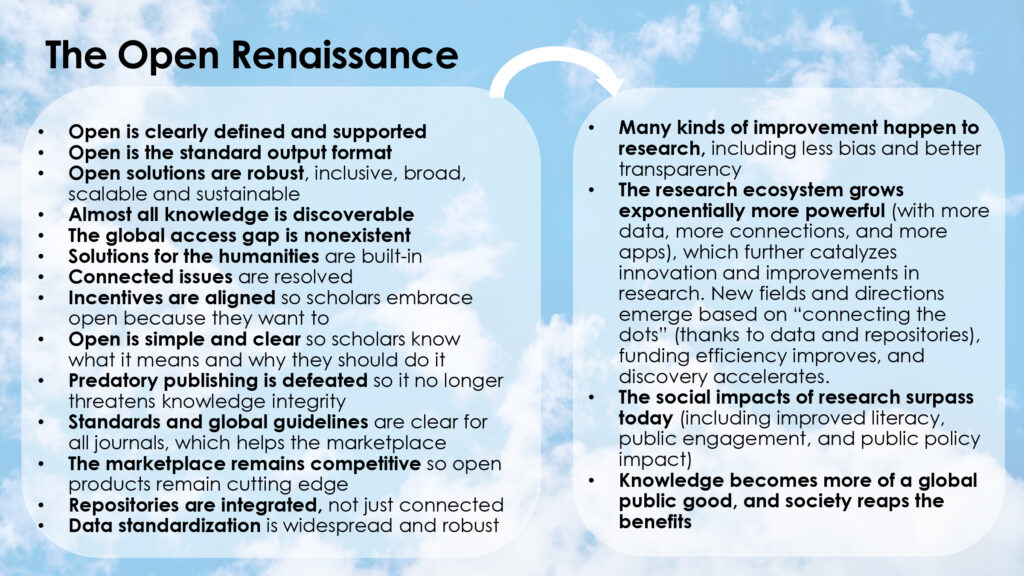

By building on this foundation we can get to an “open Renaissance” in our near future. This will take patience and sustained, collaborative effort but the rewards in terms of benefit to research and society may well be more than we can imagine (see figure 3).

Conversely, by continuing along the path that has been more frequently traveled in this space—pursuing out of necessity regional, partial and non-inclusive solutions while also failing to adequately address systemic issues like impact factors—we may realize much less benefit from open and even end up with a stalled future for scholarly communication where common action becomes impossible, enthusiasm for collaborative effort on connected issues drops, and researchers increasingly cling to less open but more “proven” formats because it’s in their best interests to do so (Hampson 2018a).

What might a “collective effort” on Plan S look like? Some in OSI are ready to support this plan as-is, some are not. In the latter group’s estimation we need to carefully think through this proposal and its potential ramifications before moving forward. From all sides, though, there is undeniable enthusiasm and interest in the fact that the scholarly communication community may be “finally” starting to take steps toward improving open on a broad scale, so this enthusiasm and interest should be embraced.

Therefore the first and most important collective effort is to ensure that the road ahead for Plan S includes room for dialogue. OSI is ready and willing to help with this. UNESCO, for instance, has suggested convening a meeting of Plan S leaders and international scholarly communication stakeholder leaders at the earliest convenience. Deciding what comes afterward for Plan S should grow out of these conversations (or something similar).

As for common ground, this dialogue is sure to reveal a lot of it. For years now the debate in the scholarly communication community about the future of open has been divisive and acrimonious, which has left many with the impression that there is an utter lack of common ground on key issues and no hope for collaborative solutions. In our experience, however, there is a lot of common ground—we just haven’t spent much time there yet.

With specific regard to Plan S almost half (46%) of OSI survey respondents support this plan with minor or major changes—and 62% support it as-is, with minor or major changes, or the idea of this plan but not this plan itself. In all, the overwhelming majority of respondents support reform toward a world with more open although not necessarily global, immediate or total reform. If these opinions are reflective of the broader stakeholder community then there is a lot of common ground about at least the sentiments of Plan S.

The devil is in the details of course, but these details—these specific plans and policies—can and should be worked out by the scholarly communication community. Some possible areas of common ground are identified in table 3.

It’s important to note that the patches of common ground identified in table 3 are only general and illustrative—they are just observations about possible overlaps of interests, concerns and criteria, and are not specific solutions. This point is key. Detailed common ground solutions can only be developed and cultivated by all stakeholders in scholarly communication working together. These solutions cannot be invented and imposed by OSI, by funders, or by any other outside body that isn’t truly representative of this diverse ecosystem and that isn’t carefully weighing all perspectives and endeavoring to arrive at measured, balanced conclusions.

Indeed, the scholarly communication landscape is so complex that only the entire community working together can arrive at the right solutions. This point is echoed by the aim and scope language of the Plan S guidance and implementation document wherein Plan S organizers recognize “that research funders, institutions, researchers, learned societies, librarians, and publishers must work together towards a system of scholarly publishing that is more accessible, efficient, fair, and transparent.”

If we are all sincere about this sentiment, we should bring this symphony of voices into the planning process as a first step and only then start working together to unlock the promise and potential of open. From this vantage, Plan S can be an important bridge to the future.

Finally, this same sentiment should apply not only to developing the details of our new plan for the future of global open, but to improving our understanding of the open landscape as well. On this landscape, “open” is an important means to an end, not our final destination. The research communication challenges of today will be solved, data and content will be open and new challenges will emerge that we can’t fully envision yet—evolving educational models, changing roles for universities, an increasing role for artificial intelligence and machine learning and so much more.

Our devotion to this landscape is incredibly rich common ground. We owe it to ourselves, to research, and to society to begin exploring this common ground together.

TABLE 3: PLAN S COMMON GROUND (ILLUSRATIVE ONLY, NOT NECESSARILY ACTUAL SOLUTIONS)

| PLAN S principles & technical guidance | OSI common ground observations | |

| High-level perspective | ||

|

Agreed | |

| Specific Plan S principles | ||

| Goal statement | After 1 January 2020 scientific publications on the results from research funded by public grants provided by national and European research councils and funding bodies, must be published in compliant Open Access Journals or on compliant Open Access Platforms. | OSI broadly supports all open initiatives that are testing and exploring ways to improve open. As a regional plan specific to the EU, OSI participants have been less inclined to comment; the EU has tried a number of regional approaches for years. |

| 1 | Authors retain copyright of their publication with no restrictions. All publications must be published under an open license, preferably the Creative Commons Attribution Licence CC BY. In all cases, the license applied should fulfil the requirements defined by the Berlin Declaration; | Agreed, but also consider more flexibility here going forward. Free to read vs. free to reuse has been viewed by many as a speed bump on the road to rapidly achieving more open. According to numerous surveys and studies, CC-BY licensing has not been popular with many authors (see T&F survey, Solomon, Tenopir, and others), plus it works better in some fields than others. This may be a sticking point in the growth of open—not everywhere, but enough to raise concern about the viability of any plan that depends on achieving 100% compliance with CC-BY (or its variants). What if we stick to our ideals about reuse—continuing to strive for and reward CC-BY—but at the same time allow ourselves more flexibility in the here and now and take a broader approach to open, acknowledging that many types of open have emerged over the last 20 years? In doing this, we can focus first and foremost on improving access—on making as much of the research world as “free to read” as possible (especially research of the most time-critical importance, such as in medicine). Over time, we can improve OA education and advocacy, open data requirements and use, and more, and also let these newly open instruments develop a critical mass, a greater following, value-added components, best practices, and so on, such that being more invested in open (including free to reuse) clearly makes sense to researchers and increasing the degree of open is in their best interest. |

| 2 | The Funders will ensure jointly the establishment of robust criteria and requirements for the services that compliant high quality Open Access journals and Open Access platforms must provide; | This idea is important and valuable, but instead of having these requirements emanate from funders, consider instead creating a global, representative working group to develop the compliance standards required by this plan, and make this group accountable to an international body like UNESCO (or create a new body for this purpose). In addition, consider helping the global publishing industry develop collaborative plans and structures so it can police its own (similar to insurance industry groups, NISO, etc.). |

| 3 | In case such high quality Open Access journals or platforms do not yet exist, the Funders will, in a coordinated way, provide incentives to establish and support them when appropriate; support will also be provided for Open Access infrastructures where necessary; | Agreed, but again, maybe don’t rely only on funders to do this work. Instead, invest a significant amount in improving open infrastructure and publisher capacity building. In particular, consider approaches such as (1) developing new global solutions to indexing, (2) investing in a global science cloud (perhaps built off EU’s current version—global conversations about this cloud should be facilitated), and (3) investing in SciELO to facilitate its expansion, and/or, investing in the development of SciELO clones in Sub-Saharan Africa, CAMENA, and SE Asia. |

| 4 | Where applicable, Open Access publication fees are covered by the Funders or universities, not by individual researchers; it is acknowledged that all scientists should be able to publish their work Open Access even if their institutions have limited means; | This sentiment seems broadly acceptable. However, whether it can actually translated into workable policy is a question that needs to be investigated. Many researchers and their institutions have very limited means. These capacity gaps are poorly understood. Therefore, we need to research these gaps in order to better understand what’s needed to help institutions and disciplines become more open. With regard to Plan S, we should study the capacity of the global south to publish under an all-APC system (and also study and model how/if APC waivers will work). Also, investigate the capacity of Research4Life to expand subscription access in the global south since they only provide access to institutions and it is difficult for individuals not located at institutions (like clinicians) to gain access (and if this program needs more money, provide it). |

| 5 | When Open Access publication fees are applied, their funding is standardised and capped (across Europe); | Carefully research the APC price controls idea before implementing it (or drop this idea altogether if indicated). Market signals will drive some APCs higher and some lower; artificially flattening these signals may lead to choice distortions and unintended consequences. There may be other ways to shed light on pricing, such as creating a robust comparison-shopping site for APCs (although comparison shopping doesn’t seem to be happening at the moment, so incentivizing researchers to comparison shop may also be needed). |

| 6 | The Funders will ask universities, research organisations, and libraries to align their policies and strategies, notably to ensure transparency; | Policy alignment should of course happen in an ideal world. In reality, incentives will probably need to be aligned before policies can be aligned. In this case, Plan S will probably need to prove itself first before it gets broad buy-in, but it can also help achieve this buy-in by asking researchers to help develop the plan. As for improving transparency, this is a key goal of Plan S. Even though the suggested method of achieving this (i.e., by publishers opening their books) may be ultimately unworkable, figure out some way of doing something along these lines in order to facilitate more productive dialogue between publishers and funders. |

| 7 | The above principles shall apply to all types of scholarly publications, but it is understood that the timeline to achieve Open Access for monographs and books may be longer than 1 January 2020; | A key lesson from OSI discussions has been that one-size-fits-all approaches do not work in scholarly communications. While the temptation to leave difficult solutions for the humanities and social sciences until later is understandable, truly workable global solutions to scholarship should try to address everything from the outset. These solutions cannot apply to “all types” of scholarly publications while also exempting a great many of them, or force-fitting them later with solutions designed for STM. |

| 8 | The importance of open archives and repositories for hosting research outputs is acknowledged because of their long-term archiving function and their potential for editorial innovation; | Pre-print servers are increasingly popular and valuable and may portend the future of scholarly communication. However, existing and rapidly growing servers like bioRxiv are currently noncompliant with Plan S—technically, and also in terms of containing a wide variety of articles, not all of which are CC-BY and/or versions of record (or AAMs). All preprint servers should be accepted and innovation in this space encouraged (see also the comment about principle 2 with regard to letting the international community design new standards instead of funders). |

| 9 | The ‘hybrid’ model of publishing is not compliant with the above principles; | Hybrid costs are a concern. So too are subscription costs and open costs. Cost concerns clearly need to be addressed, somehow. However, the “Aim and Scope” preamble to the Plan S implementation guidance documents states that this plan “does not favour any specific business model for Open Access publishing or advocate any particular route to Open Access given that there should be room for new innovative publishing models.” Therefore, this principle of banning hybrids is inconsistent with the aim and scope guidance. |

| 10 | The Funders will monitor compliance and sanction non-compliance. | Mandates in scholarly communication have a mixed record when they’re too stringent (for the most recent compliance accounting for the UK, see Research England 2018). Maybe we can we be more creative here, like using compliance incentives—offering more funding for open publishing, or rewards to authors and institutions who publish more open? Funding an “OA Nobel Prize” or “OA X-Prize” has also been proposed by OSI participants as one way of drawing attention to open and flipping the conversation from compliance-based to innovation- and benefit-based. |

| Plan S technical guidance | ||

| Sections 9, 10 and 11 of the Plan S technical guidance document contains detailed recommendations on future publishing guidelines, transition plans, and more. As per OSI’s observations on principle 2, above, these technical guidance sections might be developed by (and accountable to) the international scholarly communication community instead of just funders. Some possible areas of common ground with regard to technical guidance are noted to the right. |

|

|

| Additional elements for consideration (recommended by OSI participants) | ||

| Plan S is silent on a number of focus areas that OSI supports. These areas are listed to the right. |

|

|

TIMING

This is a fast-moving issue. A taskforce put together by Plan S organizers issued implementation guidance for the plan in late November 2018 (see the Plan S website). Public comment closed on February 8, 2019. In other news:

- China, as noted previously, recently indicated it supports the principles of this plan. The National Library of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Chinese National Science Foundation, and the National Science and Technology Library all presented written statements endorsing this view. In China, however, the value proposition of open access may center more around improving quality, credibility and transparency than improving public access (Montgomery 2018), so weighing the pros and cons of Plan S may be different for China than for the EU (i.e., on matters like reducing fraud and improving quality, Plan S is strong).

- The UK appears to be in no rush, with the UKRI indicating that “Any implementation of Plan S principles by UKRI will be subject to the OA Review. This includes the Plan S principle around the standardization of publication fees and funding across Europe. Costs and benefits around OA models and impacts arising from proposed changes will be considered as part of the OA Review, including sustainability, with wider economic impacts considered by BEIS. The OA Review will report in 2019.” (Harrington 2018)

- It is unclear whether Germany’s constitutionally-protected academic freedom will prohibit the country from joining Plan S.

- In the US, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued a major open access directive (the public access decision described earlier) in February 2013. Since then, US agencies have gone to great effort and expense to comply with this directive. Whether the US now adopts Plan S in favor of its public access approach will likely be OSTP’s decision to make.

REFERENCES

The following resources are cited in this body of this report, but these represent only a portion of the resources OSI has reviewed:

- AAP. 2018 (Nov 8). AAP, Researchers, Deeply Concerned About Plan S. Association of American Publishers

- AHA. 2019 (Feb 4). AHA Expresses Concerns about Potential Impact of Plan S on the Humanities. American Historical Association

- APE. 2019. Academic Publishing in Europe 2019 conference website

- Archambault, É, D Amyot, P Deschamps, AF Nicol, F Provencher, L Rebout, and G Roberge. 2014. Proportion of open access papers published in peer-reviewed journals at the European and world levels–1996–2013. European Commission

- Archambault, E. 2018. Universalisation of OA scientific dissemination.

- Barrett, K. 2019 (Jan 24). Email exchange with Kim Barrett, Editor-in Chief, Journal of Physiology

- Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing. 2003.

- Binfield, P. Novel scholarly journal concepts

- Björk, BC. 2018. Evolution of the scholarly mega-journal, 2006–2017. PeerJ 2018; 6: e4357. doi:10.7717/peerj.4357

- Clarke, M. 2018. Plan S: Impact on Society Publishers. The Scholarly Kitchen

- COAR. 2018 (Dec 13). COAR’s Feedback on the Guidance on the Implementation of Plan S. Confederation of Open Access Repositories

- Cochran, A. 2018. Plan S: A Mandate for Gold OA with Lots of Strings Attached. The Scholarly Kitchen

- Crawford, W. 2015 (Oct). The Gold OA Landscape 2011-2014. Cites & Insights, 15:9

- Eger, T and M Scheufen. 2018. The Economics of Open Access: On the Future of Academic Publishing. Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.4337/9781785365768

- Ellers, J, T Crowther, and J Harvey. 2017 (Oct). Gold Open Access Publishing in Mega-Journals. Journal of Scholarly Publishing. doi: 10.3138/jsp.49.1.89

- Else, H. 2018 (Jul 19). Dutch publishing giant cuts off researchers in Germany and Sweden. Nature