History books point to the 2001 meeting of the Budapest Open Access Initiative as a seminal event in the history of open. Often lost in this lore, however, is the fact that open has long been an active and evolving field and that many organizations and efforts have histories that predate 2001. At least four major open organizations started in 1998, for instance, and celebrated their 20th anniversaries in 2018: PLOS, J-Stage, PKP, and SciELO. And prior to 1998, there were visionary efforts and investments being made by other organizations laying the groundwork for today’s open—-including the launch of arXiv in 1991, and investments by FAPESP (Brazil’s leading science funding foundation) in open starting in 1988. These organizations continue to thrive and are at the leading edge of open evolution today.

Last week, ScieELO celebrated its 20th anniversary by bring more than 600 leaders from across scholarly communication (including 10 from OSI) to Sao Paulo to discuss the current state of SciELO and the future of scholarly communication. Many consider SciELO to be the world’s most successful example of a decentralized, researcher-led journal platform. The Brazil-based network manages 1285 journals, mostly from Latin and South America, that together have published 650,000 articles which are accessed 800,000 times per day and have received 1.1 million citations. Largely due to SciELO, Brazil leads the world in the proportion of its science published in open format (about a third of the country’s total output; 80% of SciELO publications are open) and the number of citations per article.

Last week, ScieELO celebrated its 20th anniversary by bring more than 600 leaders from across scholarly communication (including 10 from OSI) to Sao Paulo to discuss the current state of SciELO and the future of scholarly communication. Many consider SciELO to be the world’s most successful example of a decentralized, researcher-led journal platform. The Brazil-based network manages 1285 journals, mostly from Latin and South America, that together have published 650,000 articles which are accessed 800,000 times per day and have received 1.1 million citations. Largely due to SciELO, Brazil leads the world in the proportion of its science published in open format (about a third of the country’s total output; 80% of SciELO publications are open) and the number of citations per article.

The first day of the SciELO-20 conference featured a series of parallel workshops for SciELO network members, focused on improving the network’s journals through good editorial practices and a transition to open science. The second day featured presentations on workshop outcomes. The final three days were the public portion of this event focusing on open science writ large, kicked off by video greetings from Harold Varmus, John Willinsky, Robert Jan-Smits, and Jean-Claude Guedon who all acknowledged the importance of SciELO’s pioneering work and the organization’s influence on the future of scholarly publishing.

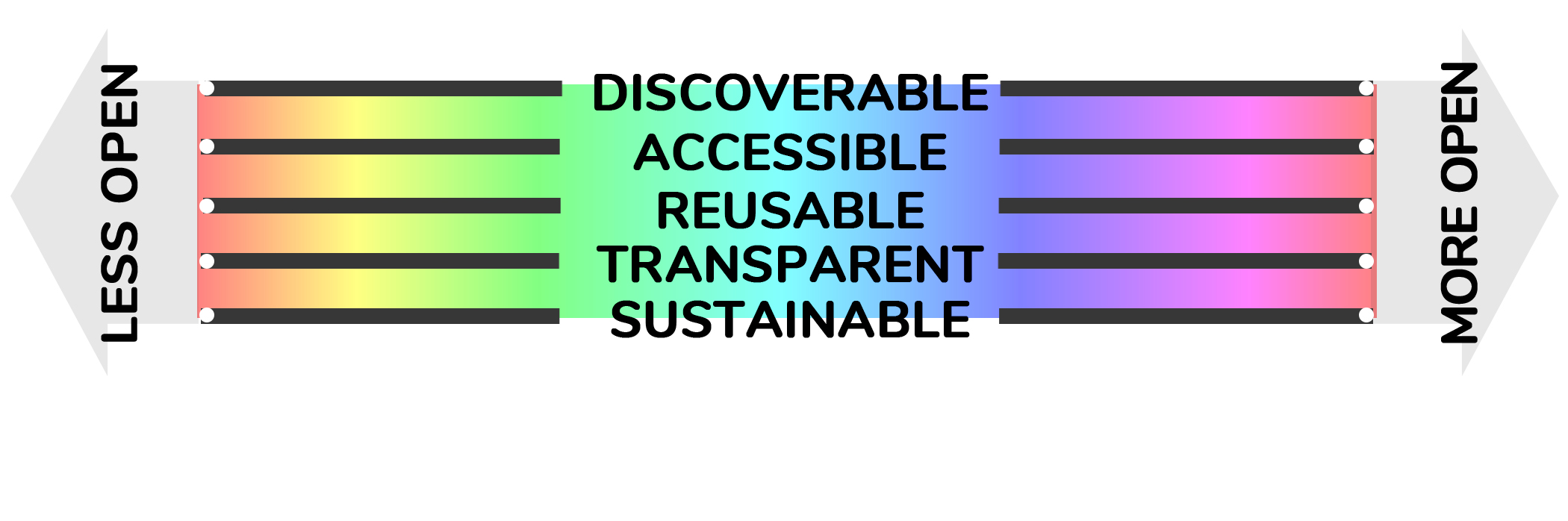

What was learned from SciELO’s week of reflection and prognostication? By design, the central organizing theme of the conference was knowledge as a global public good. But several other common themes emerged throughout the week that were unexpected and ran counter to what is often presented as prevailing wisdom in scholarly communication. For instance, a number of presenters emphasized the fact that we don’t really speak the same language when it comes to open. “Open” has no common definition—it has been appropriated by open data, open source, open education, and even within scholarly communication to mean many different things, and rarely “open access” as defined by the Budapest (BOAI) guidelines—free to read, free to reuse, and immediate (not delayed by embargo). Rather than trying to create a definition that spans every current variation, OSI has instead proposed that “open” is actually a range of outcomes that fall along a broad spectrum. These outcomes are typically described by different colors (green, gold, bronze, etc.) but there are far more variations of open outcomes than colors can reasonably label. OSI recommends simply embracing the open spectrum to acknowledge these outcomes (see figure below). In this spectrum, open outcomes vary along five dimensions (discoverability, accessibility, reusability, transparency and sustainability); outcomes near the far right—since these are free to read, free to reuse, and immediate—are more likely to meet the strict BOAI definition of “open access.”

It is very important to note here that “open” does not mean the same thing as “open access.” These two terms are frequently used interchangeably, and the end result is that we often end up talking past each other when we say “open” is growing this fast, or “open mandates” have this level of compliance or that, when in fact we may actual be talking about different things. Developing a common vocabulary is a critical first step in being able to collaborate more effective on the future of open.

This is why it was significant to see so many of the experienced practitioners of open at SciELO not take a hardline view about the orthodoxy of open, which holds that anything not free, immediate and CC-BY is in fact not truly open. The vast majority of the open spectrum contains “flawed” open, but there wasn’t any disagreement that these flawed materials, while less than ideally open, were still functionally open (that is, they were discoverable and free to read), and should therefore be counted as progress toward open. This is not to say that we have shifted the goalposts to make open easier. Rather, people are acknowledging that materials which are free to access and read but may still carry a copyright notice have tremendous practical value, and that having free access to these materials is far better than not having any access at all. Also, once on the spectrum, the community can get a better sense of the true scope of open and work to improve the openness of all collections accordingly.

Along these same lines, “open science” and “open access” do not mean the same thing either. These terms are also often used interchangeably. Open science covers a broad range of inputs and outputs. Here again, being in favor of open science means being in favor of working to improve a very broad spectrum of inputs (peer review, replicability, etc.) and not just “making science outputs open access.”

Highlighting two other semantic barriers, several speakers zeroed in on the concept that open access isn’t our central organizing principle, but instead, it’s our commitment to improving science. Open access is a tool for improving science, not the goal. And several speakers noted that science needs interoperability, visibility and credibility, but that these things mean (and are defined) differently by different people. Some see these goals through the lens of metrics; other see these goals as being more qualitative in nature.

Open data was another widely addressed topic at SciELO-20. We are truly at the infancy of open data. FAIR standards are just a start (where data must be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable). There is so much more that we don’t know yet about how to make it possible for different data to be usable— data preparation expectations and assistance, standards, instructions for how to use the data (to guard against data misinterpretation), and much more. Barend Mons’s identified “7 deadly sins” of modern scholarly communication, and three of these had to do with data: we publish papers without data and vice versa; our current method of paper first publishing creates a nightmare for machine readability; and we create data without a stewardship plan.

Four other sins identified by Mons resonated across several other presentations: we brush aside complexity and look for simple solutions; we disrespect disciplines outside our own (journals are silos by definition); we refuse to invest in modernizing our research infrastructure; and we use the impact factor as a proxy for importance.

Impact factors were sharply criticized by almost all presenters (except those who were describing their metrics products and services) for how these statistics are misused in science and how they distort science decisions and distract from focusing on making better science. Defenders contended that metrics are necessary and important—different stakeholders (funders, researchers, etc.) need and value different kinds of metrics. One suggestion presented during the Q&A involved turning metrics from being a tool for external validation into a tool for internal improvement. If an article is “underperforming” according to its metrics, we can use this information to improve the article (its structure, metadata, tagging, density, writing style, language, and more), improve its visibility and discoverability on the repository where it resides, and/or improve the outreach effort that accompanied this work. In other words, we can use metrics to help make science better, not to judge scientists and their work. Ultimately, the utility ends up being the same—science funders get to see how studies are reaching their markets, and authors get to see how their work is being socialized into science. The biggest difference is that the outcome of an “impact factor flip” is to close the feedback loop and actually do something with this data to help improve the product. It’s what we do all the time with retail websites. Why not with journal websites as well?

Finally, FAPESP’s scientific director Brito Cruz noted that in scholarly communication, “The north has ‘challenges’; the south has ‘problems.’” Cruz highlighted how we continue to think of science from the global south as being a lower quality product, and treating it as such (via less indexing), which makes it less visible (via fewer citations). We need to break out of our north-sound science mindset which stigmatizes and excludes and instead just start focusing science. In a follow-up to this concern, OSI participants discussed this issue this week and suggested that if we need to create “categories” of research that recognize which regions of the globe are being well-represented and which are not—a categorization we may need to make if we’re trying to improve global equity in scholarly communication outcomes—then maybe the number of papers published per country would be a better metric than economic output. According to Scimago, considering the total scholarly works published by country between 1996 and 2017, our “Big 5 Research Countries” would be the US, China, UK, Japan and France—which together account for just over 50% of the papers published. The “Big 20” group (accounting for 83% of the total) includes five “developing” countries. And in the “Big 50“ (accounting for 97% of the total), half are “developing” countries. If we use groupings like these, we can—for instance—focus on the concerns of countries in the Big 50 with regard to leveling the playing field for indexing and impact factors, or focus on the concerns of the “Emerging 186” (the countries not even in the Big 50) with regard to capacity building.

In a closely related theme, several speakers noted how cultural change is needed—what kind of communication counts toward promotion and tenure measures, whether peer review should be open instead of closed (one described the closed approach as a “bastardization” of the intent of peer review), whether researchers’ fear of being scooped can be alleviated through broader use of pre-print servers, and more. Can we embrace “living” articles that are a version of record, a record of versions, and a record of the version of record? Can we have “coope-tition” — a term coined by Louise Page—where we work together to invigorate the system? Can we align researcher incentives, and gradually evolve the system? Can we, as Eric Archambault noted, stop being so exclusive?—open, closed, north, south, English, Chinese, discipline silos, and so on. “We are all complicit in this,” notes Eric.

Other topics that featured prominently at this event include:

- Plan S: Many speakers and participants expressed reservations about the apparent rush to judgment on this plan. There was a palpable sense that the global effects of this effort had not been adequately considered and that more careful deliberation was needed. Overall, in a room filled with open advocates, the enthusiasm was somewhere more than muted and less than qualified.

- Pre-prints: In contrast to Plan S, the enthusiasm for pre-prints was palpable and widespread. SciELO also highlighted its agreement with PKP to develop a pre-print capacity for SciELO journals.

- Texture: The JATS XML-editor Texture was introduced at this event, and launched live as open source freeware to much applause. Texture should significantly simplify journal markup work, making it easier for editors to optimize articles for broad discovery and sharing.

There is much more, of course—this description isn’t a full accounting of what was discussed at SciELO’s 20th anniversary event, but these were the highlights and common threads. For more information, please visit the conference website at scielo20.org. In all, this was a richly diverse event not normally seen outside of venues like Force11 and OSI, and is a testament to SciELO’s commitment to forge a workable and sustainable path toward the future of open.