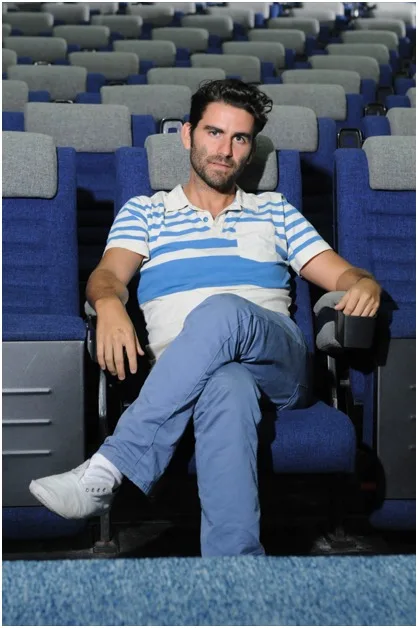

Alexis Gambis is a French-Venezuelan filmmaker with a PhD in molecular biology. His debut feature The Fly Room tells the story of geneticist Calvin Bridges (of the TH Morgan lab) and his relationship with his estranged daughter and will premiere on the festival circuit later this year. Gambis is the founder and artistic director of Imagine Science Films, a NYC-based nonprofit that organizes science-themed film festivals in cities around the world. He’ll be previewing his film at the Genetics Society of America’s 55th Annual Drosophila Research Conference later this March. Gambis holds a BA in biology from Bard College, a MA in Bioinformatics from L’Universite Paris-Est de Marne Le Vallee, a doctorate in Molecular Biology & Genetics from Rockefeller University, and a MFA in film from NYU. He’s currently teaching courses that incorporate both science and film at NYU’s Abu Dhabi campus. Gambis’ films often use surrealism and abstract scientific imagery to explore the inner lives of scientists, which sets him somewhat apart from mainstream depictions of science. He’s an outspoken advocate for interdisciplinarity and works hard to create spaces where art and science can be in dialogue together. We sat down with Alexis to ask him a little bit more about his approach to depicting science and what he thinks scientists and educators can do to promote science communication.

Alexis Gambis is a French-Venezuelan filmmaker with a PhD in molecular biology. His debut feature The Fly Room tells the story of geneticist Calvin Bridges (of the TH Morgan lab) and his relationship with his estranged daughter and will premiere on the festival circuit later this year. Gambis is the founder and artistic director of Imagine Science Films, a NYC-based nonprofit that organizes science-themed film festivals in cities around the world. He’ll be previewing his film at the Genetics Society of America’s 55th Annual Drosophila Research Conference later this March. Gambis holds a BA in biology from Bard College, a MA in Bioinformatics from L’Universite Paris-Est de Marne Le Vallee, a doctorate in Molecular Biology & Genetics from Rockefeller University, and a MFA in film from NYU. He’s currently teaching courses that incorporate both science and film at NYU’s Abu Dhabi campus. Gambis’ films often use surrealism and abstract scientific imagery to explore the inner lives of scientists, which sets him somewhat apart from mainstream depictions of science. He’s an outspoken advocate for interdisciplinarity and works hard to create spaces where art and science can be in dialogue together. We sat down with Alexis to ask him a little bit more about his approach to depicting science and what he thinks scientists and educators can do to promote science communication.

SCI: A lot of people talk about “art and science” or “science and culture” as if they’re two completely separate realms, but in your work, you treat them as two sides of the same coin. Art & science don’t even have to be integrated; they’re just together.

AG: Yeah. There are just so many similarities. [Art & science] are disciplines that involve both technique and creativity. When you’re doing artwork, whether it’s film or studio arts, there’s the technique of “How do you make a movie? How do you film that? How do you capture that?” And in science, it’s “How do you do a DNA prep or how do you look through the microscope?” But there’s also the creative part of “How do you craft a hypothesis? Or how do you craft a story?” It’s very similar, and there’s no end to it. In both art and science, there’s no definite final end product, and you’re constantly editing, either editing footage or editing experiments so that they fit into the story. And both [artists & scientists] are extremely passionate types of individuals.

SCI: How did you arrive at that worldview? Because it seems to run counter to the way science is portrayed in mainstream media.

AG: I was always interested in science from an early age, but I was never very interested in the numbers. I was interested in it from an aesthetic point of view. And I think a lot of that comes from the fact that my dad was an engineer who became an artist. My dad’s art space was my living room, so I basically grew up in an art studio. His work was very abstract but sometimes it would incorporate these equations, and I always remember that whenever I was having trouble with my science homework, my dad was really good at math and doing scientific work and yet, he was a painter. So it was very normal that those two worlds [art & science] were together. Bard [the college where Gambis went to undergrad] is really where things started for me. In high school, I was in a French system, and it was very rigid. You really needed to know exactly what you wanted to do, and I was doing biology but I couldn’t quite figure out what I wanted to do. Bard allowed me to take art classes. I remember I had a teacher who told me that I wasn’t very good at drawing portraits, but I was very good at drawing trees. And it was interesting because at the time I was very into nerve connections, and I was really interested in neuron science. And he told me that my branches were like amazing. Bard was great, but at the time when I was at Bard, I wasn’t really combining them. It was more like separate interests. I was taking biology classes and film classes, but I hadn’t quite figured out how to blend them yet. So then I went on to do a PhD at Rockefeller University, and I remember the day that I finally figured out that I was interested in the aesthetics of science but I not that interested in science in terms of getting results. I realized that what I really wanted to do was communicate the aesthetics of science and the stories and the anecdotes and have a big emphasis on how things are visualized without necessarily having to over-explain everything. I like just having visuals and having people infer their own explanation about what this visual means. At first I started taking photos of abstract biological structures and made a calendar out of that. I remember I had so much fun with these forms where you couldn’t really tell what they were, but they had all these colors and shapes. What’s interesting is my dad got inspired by some of that, and there was this whole period in his painting where he was doing that. I wasn’t like, “I’m going to make films that document the research I’m doing!” I was more into the idea of creating fictional stories in the lab environment using what I had. And when I would talk to people about what I was doing with my life, it was like, “I can’t really explain. You may not understand why I spend 8 hours a day looking at flies under a microscope, but here’s a movie. Here’s my lab. Here’s what I do.”

And then as I was doing that, I realized that I was very frustrated by how science was portrayed in movies and mainstream media. I guess I didn’t notice it as much until I started making movies, and then I was like, “God, there’s so much to explore, but I feel like everything is so limiting in terms of how it’s communicated,” and so the idea just came up: What if we started a film series and we tried to get scientists to make movies? And that was Imagine Science. It expanded and became a bigger thing with the film festival, but Imagine Science was my way of creating my own house, where I could do those things.

SCI: What do you think are some of the shortcomings of the way science is usually represented in mainstream media?

AG: A lot of the mainstream stuff is very safe and very standard and conventional. I don’t claim to be good at what I do, but when I started on my projects, I wanted to push boundaries. Filming became like an experiment: What if we were to make the fly an actual character that experiences things? What if we were to shoot the whole lab from just the fly’s point of view? What if we used surrealism? In my early days of experimenting, I got frustrated with actors. I was never really happy with method actors and I just remembered being in auditions and thinking, “What if we just had scientists play this? What if the actors were scientists?” What if we had them scripted but also let them bring in their own ideas? What if they were to play alter-egos of themselves? Of course, it helped that I’m a scientist myself. If I were just somebody coming out of nowhere being like, “Hey guys, I want you to be in my film!” they would maybe be more skeptical but the fact that I’m a molecular biologist, I think that helps people to feel more comfortable in terms of opening up. Once you get them in a safe spot, you can really start to experiment. Even if it’s a Nobel laureate, once you have that level of trust, they trust how you’re going to use the footage. It’s especially important [to build trust] with scientists, because oftentimes they get interviewed by the press, and then the press completely distorts what they say for some controversy or some breakthrough. When I’m with them, I tell them, “We’re not going to talk about your research.” I’ve started to think of working with scientists, before my movies, I had a film series at Rockefeller called Portrait of a Scientist, and I would interview all these scientists at Rockefeller. I would sit with them, and they’d be expecting the normal interview questions like “What do you do? Tell me about your research and your background,” and I’d ask them things like “What do you do when you’re not at a lab?” or “Tell me why you’re obsessed with teeth,” or “Explain to me how your desk is organized.” So weird questions but that would put them a little bit off balance, but I was more interested in their character, who they were, and suddenly Paul Nurse was telling me that he was an amateur pilot, that he had his own air strip. And all these side stories that were really fun.

SCI: Yeah. I think that the fear of being misinterpreted is also impetus behind the “over-explaining” style of science communication. Do you ever worry that people might misconstrue the science from simply looking at the unexplained visuals in your films?

AG: Scientists are always really critical about representations of science, but I think it’s important to understand that in order to find ways of portraying science in a better way, people need to experiment and find new ways of covering different topics. Of course you need to be alert in terms of making sure that scientists are not portrayed in a bad light, but there are always going to be science people that are going to think that it’s not done properly or that there’s not enough science in this film. My films tend to have very little science, because science is usually the platform through which I get into the human drama. Like I made this film about memory and about a scientist that works on memory in rats and he’s dealing with memories of his father that died and mixing memories of his father with rats and research on rats. It’s very visual but I never get into too much science.

With The Fly Room, the main focus that I had, which is not often shown was that in scientific research before there’s any discovery, there’s the process. There’s a process of science that takes months, that takes years. When the girl walks into the lab there isn’t a major discovery that happens the day she arrives; it’s just a world of guys that are just doing their everyday activities and she hears this scientific jargon that is happening around her but there isn’t an emphasis on the discovery of genetics. It’s just two days in the lab that was the birthplace of genetics. And I’m sure I’m going to get criticism for that because I don’t emphasize the head of the lab, who got the Nobel Prize in genetics. People are going to be like, “If the film is about The Fly Room, why isn’t the film about him? And why aren’t you talking about the major discoveries in the lab?” But I’m ready to defend my film.

SCI: Speaking more broadly now, what do you think scientists can do to improve science communication?

AG: There has to be change at the teaching level in college and high school. The young generation is comfortable with the idea that science is not just about numbers and following protocols; it’s about creativity and thinking outside of the box and it’s actually much more accessible than one might think. The general media tends to create this illusion that science is very difficult or that it’s only accessible to a very few people who actually understand it. And we need classes that are very interdisciplinary. I teach a class at NYU’s Abui-Dhabi campus called Vision to Visual that combines film and neuroscience. For seven weeks, my students learn about the neuroscience of the visual system, and I teach that using film and popular culture, but obviously, it’s still pretty science-heavy. And then the seven weeks afterwards is all about visualizing science but also visualizing vision. How do we see science? How do we see vision? What are the aesthetics of science? And then at the end of the class, they all make movies. The current situation with colleges and universities and the fact that they have different departments, I think that it’s kind of hard to break that. You can have interdisciplinary programs and seminars and colloquiums and festivals and all kinds of things but these worlds will still remain divided. I’m actually a big proponent of the DIY lab movement where labs are just popping up that aren’t affiliated with academic institutions or establishments. there needs to be actual research that’s happening, that’s funded by the NIH or the NSF but that’s happening outside of the academic environment. My dream with Imagine Science in a few years would be to open up a lab called the Imagine Science Lab, which would be an actual lab that people could come visit. There would be actual research happening but also different collaborations with artists and film makers.

I also think that there needs to be more of an open-access movement. Especially with images and video, because a lot of good material ends up just sitting on computers in labs and never being seen by anybody. At Imagine Science, we’re contacting a lot of labs and trying to get videos that are basically just discarded footage and trying to highlight what’s happening in the labs through video. Especially if we’re going to have these DIY labs, it’s very important for people to have access to these basics that any scientific knowledge that’s published should be available to anybody.

The Fly Room will be premiering on the festival circuit later this year. For more updates about The Fly Room and Gambis’ other upcoming projects, follow The Fly Room on Facebook or follow @ImagineScience on Twitter.

Diana Crow is a freelance science writer. For more articles by Diana, visit her website at dianacrowscience.com or follow her at@CatalyticRxn on Twitter.